Diaspora

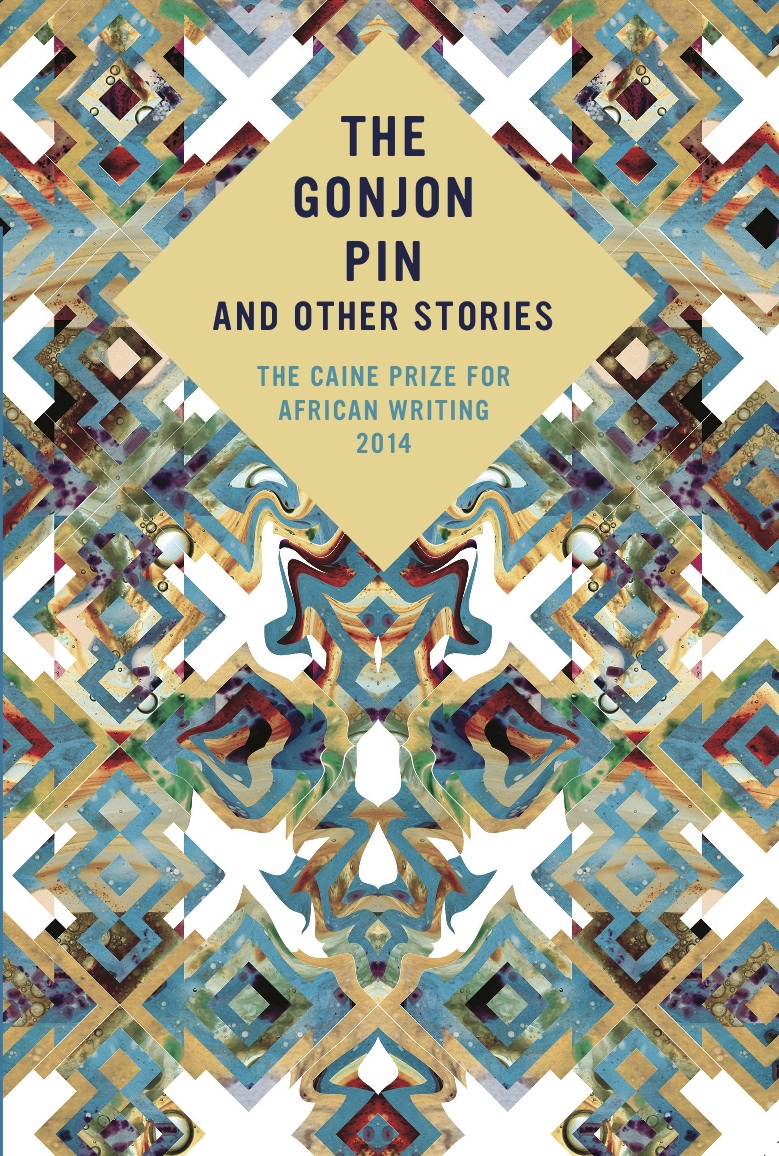

writers dominating the Caine Prize

By Rob Gaylard

A feature of

this year's Caine Prize collection of stories, A Memory this Size and Other

Stories (Jacana in South Africa, 'amaBooks in Zimbabwe), is the prominence of

what one might call diasporic stories, such as Tope Folarin's prize-winning

story, Miracle. Given the salience of novels like Brian Chikwava's Harare North

and NoViolet Bulawayo's We Need New Names, this seems to reflect an emerging

trend in African writing. (Bulawayo was the 2011 Caine Prize winner.)

A second

feature of the collection is the absence of any stories from South Africa.

Since our writers have clearly not suddenly stopped writing short stories, this

seems surprising, and may be a comment on the process of selection or the

criteria for inclusion in the collection.

There are five

short-listed stories of which four are, rather remarkably, by Nigerian authors

(or authors with a connection to Nigeria). A further 13 stories came out of

this year's Caine Prize workshop, held on the shores of Lake Victoria. Four of

these 13 stories were submitted by Ugandans.

The first story

in the collection is Folarin's Miracle - on the evidence of this story, the

author is clearly Nigerian/American. He tells us, "I'm a writer situated

in the Nigerian disapora, and the Caine Prize means a lot - it feels like I'm

connected to a long tradition of African writers."

It seems

pointless to debate whether someone who was born in America can be described as

an "African" - one infers from the story that the author's

Nigerianness is an important part of his identity, and he falls squarely within

the definition of "African writer" inscribed in the Caine Prize

rules.

The story

explores the issue of faith and belief, and provides a vivid first-person

account of a revivalist service at which a blind prophet performs what are

alleged to be miracles. The story does not confirm that any miracle has taken

place - but it does affirm the ties of family and community, and suggests that

"both (truths and lies) must be cultivated for the community to

survive".

The

congregation consists entirely of Nigerian exiles or sojourners in America, and

the story balances the narrator's scepticism against the repeated affirmation,

"We need miracles".

The American

connection is reinforced by the second story in the collection, Pede Hollist's

Foreign Aid. The story is a deftly narrated, somewhat ironic, cautionary tale

about the folly of the "Been-to" who imagines he can return to his

native land (in this case Sierra Leone), rather like a deus ex machina, putting

right whatever is wrong and making up for his 20-year absence (and neglect of

his family).

As the story

unfolds the scales are lifted from Logan's eyes and he comes to realise the

futility of his efforts. His sister, Ayo, points out, "Out here. We

manage. We do what we have to do". The story could have been subtitled The

Americanisation of Balogan/Logan: it explores the dissonance set up by the

manners and expectations of the returnee, Logan, the "self-made man from

ICU (the Inner City University)", whose "fanny pack" of dollars

rapidly runs out. One quotation will help to illustrate the inventiveness of

the writing:

"Logan was

left severely to himself. He felt powerless, useless like a kaka bailer who

arrives at a large family latrine with only a small tamatis cup, unable to and

incapable of handling the crap that had been generated."

Ironically,

much of the "crap" has been generated through Logan's efforts to

assist his family.

In contrast,

Elnathan John's Bayin Layi, set in a Hausa-speaking and predominantly Muslim

part of Nigeria, plunges us in media res. The narrator is Dantali, one of a

group of homeless boys who sleep under the kuka tree in the town of Bayan Layi.

These boys

"like to boast about the people they have killed". We are introduced

to their seemingly amoral perspective: without the security or guidance of home

or parents, they are easily sucked up into what seems to be standard

election-time violence in Nigeria.

Driven by

desperation or greed, they stop at nothing; in their hands machetes become

lethal weapons. They seem to have internalised the worst aspects of the society

around them. These include ethnic hatred (one boy is killed partly

"because he has the nose of an Igbo boy") and homophobic violence

(another victim is referred to as "a disgusting dau dauda" (or

effeminate homosexual).

The effect of

the plain, unvarnished narrative is chilling: "I am not thinking as we

move on, burning, screaming, cutting, tearing. I don't like the feeling in my

body when this machete cuts flesh so I stick to the fire and take the matchbox

from Banda." At the end our narrator is running "far, far away from

Bayan Layi" - but to what possible future? The references to Allah and the

call of the muezzin form an ironic backdrop to the grim action of the story.

Chinelo

Okparanta's America is, as the title suggests, another of the diasporic stories

in the collection. The action of the story is located in or near Port Harcourt,

in the oil-rich Niger delta region of Nigeria. America features as a kind of

promised land, a longed-for utopia. The narrator is Nnena Etoniru, a high

school science teacher, who hopes to obtain the magic green card that will

allow her to join her lover, Gloria Oke, in the US.

Two central

themes weave through the story: first, there is its restrained, understated

treatment of the narrator's same-sex relationship with Gloria; second, there is

its more overtly foregrounded environmental theme. The delta was once filled

with mangroves: "birds flew and sang in the skies above the mangroves? Now

the mangroves are dead, and there is no birdsong at all. And of course there

are no fish, no shrimp, and no crab to be caught." Young children emerge

from the waters of the creek coated with oil. Oil, in fact, runs like a

leitmotif through the story: the Gulf oil spill creates an ironic link between

America and Nigeria and provides a pretext for Nnena's visit to America (she

hopes to study the methods used to deal with the oil spill and apply them back

home in Nigeria.)

In fact, the

narrator's motives are mixed, and she is more torn than she realises. The story

concludes with a deliberately ambiguous, open-ended folk tale. It skilfully

links seemingly disparate issues, and deepens our understanding of the

attraction of America. Will our aspirant eco-activist join those who have

"(got) lost in America"?

All the stories

were shortlisted for the Caine Prize. The stories in the second part of the

anthology cover a range of topics and encompass a variety of styles. A Memory

This Size by Elnathan John (again) is a simple tale simply told, dealing with

the perennial subject of loss - in this case the loss of a younger brother

through drowning. It explores a recurring dilemma: does one hold on to the memory,

or does one let it go? "So I keep his photos close, and do not fight the

sadness. I let fresh tears drop, 10 years after."

One of the most

entertaining stories in the collection is undoubtedly Stuck, in which Davina

Kawuna breathes new life into an old form, the epistolatory narrative. The

story consists of a series of rather breathless, confessional e-mails about a

"not-yet-affair", written by Nandi to her online "friend",

Connie, whose response, when it finally comes, should be entered into the lists

of famous literary put-downs.

Ecological

concerns resurface in Stanley Kenani's Clapping Hands for a Smiling Crocodile.

Set on the shores of Lake Malawi, it deals with the concerns of a fishing

community whose livelihood is threatened by the operations of an oil company.

In grandfather's words, "to us, fish is everything. If you kill our lake,

we are dead." Do they acquiesce, or do they resist, and what form can this

resistance take? Should one try to appease "a smiling crocodile".

Gender issues

are central to Wazha Lopang's The Strange Dance of the Calabash. It evokes the

stark attitudes towards women and marriage in traditional, patriarchal

Botswanan society, and contains an unexpected twist. The narrator, aged 13, is

apparently being married off to a man she does not know (this isn't the twist).

Hellen Nyana's

short but not-so-simple story, Chief Mourner, also deals with the loss of a

loved one, this time a boyfriend. The narrator finds out about the death of her

boyfriend via Facebook - and it turns out that this is no hoax. Her status is

uncertain - their relationship has not even been made "official" on

Facebook, and she is unsure about mourning etiquette. The story has more than

one surprise to spring, and repays careful reading.

One or two

stories are not really accessible to the general reader, and seem to require a

knowledge of the local context. Fortunately, most of the stories are readable

and entertaining.

The Caine Prize

is now in its 14th year, and is supported by a number of African publishers, including, in South Africa, Jacana and, in Zimbabwe, 'amaBooks. In spite of misgivings about its representativeness,

the collection as a whole lives up to Lizzy Attree's description, in her

introduction: "These are challenging, arresting, provocative stories of a

continent and its descendants captured at a time of burgeoning change."

They deserve to

be widely read. - published in South Africa's Sunday Independent on

December 1, 2013.

A Memory This

Size is available in many outlets in Zimbabwe - in Harare at the Book Cafe,

National Gallery and Avondale Bookshop, in Bulawayo at National Gallery, Induna

Arts, Tendele Crafts, Phenduka Supplies, Indaba Book Cafe and Z&N.

In the last few

years, or has it always been the case, it has become fashionable for critics

and readers to grumble about the overt socio-political dimension of most

African fiction. They have complained about clichéd depictions of Africa –

starving kids with AK47s, corruption, poverty, flies… you get the drift. The

general idea is that there is need to move from this social realist type

fiction to something less political. To buttress this argument, they point to

greater thematic diversity in the Western canon compared with what one finds in

African Literature. Now, of course, the middle-aged white American male writer

can write a long novel about his experience of suffering a catastrophic mental

breakdown because the barista in Starbucks served him a Frappuccino instead of

a Cappuccino, and people will read this and think it is profound, worthy of

critical acclaim and a piercing analysis of the human condition. The question

becomes – so why don’t African writers do this? There have been attempts to

reenvision the literary and journalistic output from the continent so we move

away from the heart of darkness narrative that has dominated the postcolonial

era. Wainaina’s How Not To Write About Africa and Selasi’s Afropolitan concept

can be viewed as important steps in this direction.

In the last few

years, or has it always been the case, it has become fashionable for critics

and readers to grumble about the overt socio-political dimension of most

African fiction. They have complained about clichéd depictions of Africa –

starving kids with AK47s, corruption, poverty, flies… you get the drift. The

general idea is that there is need to move from this social realist type

fiction to something less political. To buttress this argument, they point to

greater thematic diversity in the Western canon compared with what one finds in

African Literature. Now, of course, the middle-aged white American male writer

can write a long novel about his experience of suffering a catastrophic mental

breakdown because the barista in Starbucks served him a Frappuccino instead of

a Cappuccino, and people will read this and think it is profound, worthy of

critical acclaim and a piercing analysis of the human condition. The question

becomes – so why don’t African writers do this? There have been attempts to

reenvision the literary and journalistic output from the continent so we move

away from the heart of darkness narrative that has dominated the postcolonial

era. Wainaina’s How Not To Write About Africa and Selasi’s Afropolitan concept

can be viewed as important steps in this direction.

.jpg)

.jpg)