Agatha and I, by Bryony Rheam, is reproduced from https://murderiseverywhere.blogspot.com/2022/03/agatha-and-i.html

|

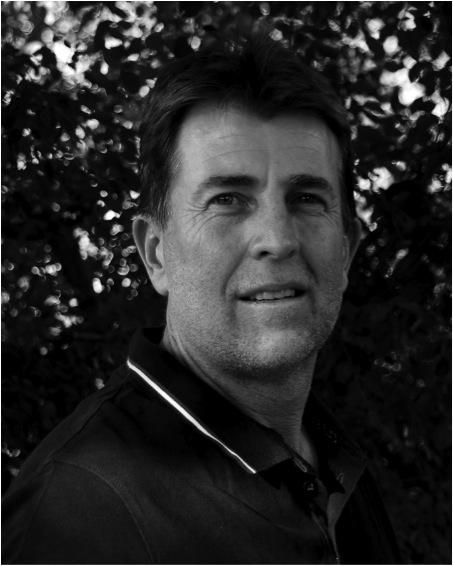

| Bryony Rheam |

Bryony Rheam is a Zimbabwean author who lives with her family in Bulawayo. Her debut novel This September Sun won Best First Book award in Zimbabwe and went to #1 on Kindle in the UK. Her new book, All Come to Dust, also an award winner, was chosen as one of ten top African thrillers by Publishers’ Weekly who described it as a “stunning crime debut”. I loved the book, and it was my pick of mysteries set in Africa for 2021. Paula Hawkins (author of The Girl on the Train) clearly felt the same way, describing the protagonist, Chief Inspector Edmund Dube, as “a fictional detective as memorable as Hercule Poirot”.That would have made Bryony’s day because of her long association with Agatha Christie’s books. Here she tells us about that and how it motivated All Come to Dust.

Welcome Bryony to MurderIsEverywhere. Michael Sears

In preparing what to write for this blog, I looked back on some old blogposts of mine where I discussed the importance of Agatha Christie in my life. One of the lines stands out for me and seems to have taken on a deeper meaning than I meant at the time. I had just finished researching Agatha Christie’s trip to Rhodesia in 1924, a trip that resulted in her writing her third novel, The Man in the Brown Suit, and I had delighted in being able to follow her on part of her journey to Bulawayo and Victoria Falls. I wrote: ‘When I began my research, I thought I was following Agatha Christie on part of her journey, but now I wonder if the journey hasn't become my own.’My journey with Agatha Christie began many years ago with my maternal grandmother. She was a lovely lady: very clever, well-read and funny. Having left school at the age of fourteen, she was largely self-taught. She loved to read, and she read anything and everything, but, in particular, she loved Agatha Christie. On Friday afternoons, I would take her books to the library for her, and I would exchange one lot of Agatha Christies for another.

She must have read them all; she must have read them two or three times, but it did not bother her. As an adult, and as an ardent fan of Christie’s myself, I now understand part of this desire to read and reread her novels. My grandmother was brokenhearted - she had lost her son in a car accident when he was twenty-one. She struggled, but she could not overcome severe depression and grief. All reading provides an escape, but with Christie it was so much more.

|

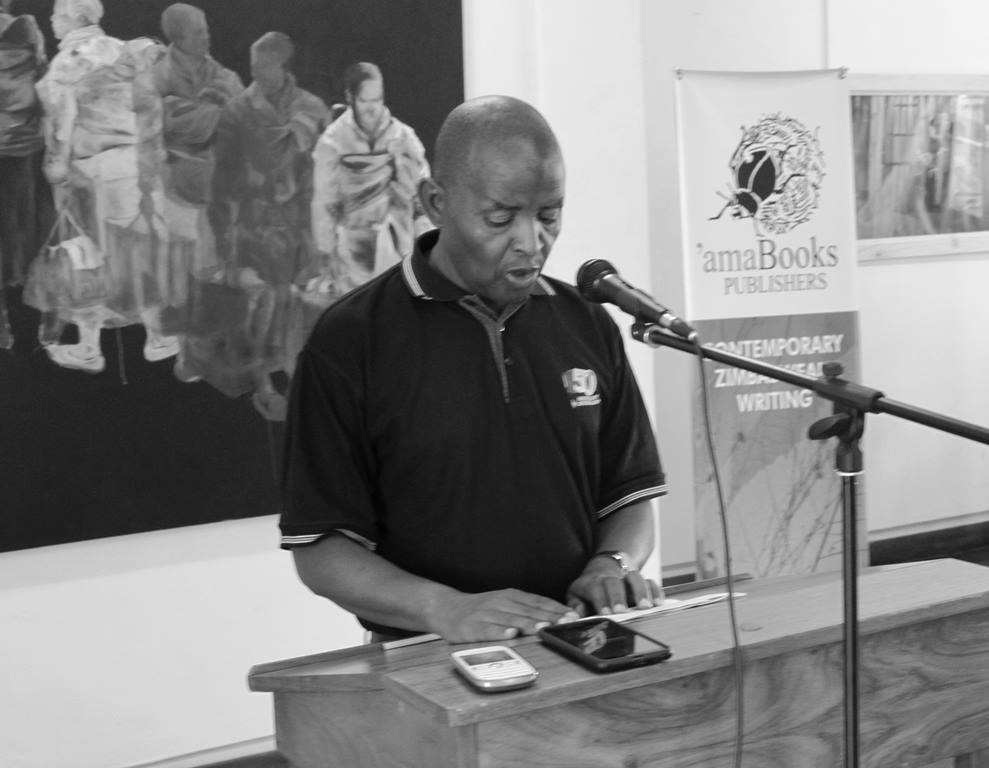

| Agatha Christie |

Agatha Christie is considered the "Queen of Crime". Although not alone in doing so, she is credited with the development of the crime novel into what we know today and its growth in popularity. She is best known for a "closed murder" story in which the crime can only have been committed by a limited number of people, each with their own particular motive for doing so. Everyone is a suspect and usually it is the least obvious person who "dunnit".

The murders are not gory; there are no detailed descriptions of prolonged deaths, the pain and injuries inflicted or the mutilated body. That is not important. What is, is the method and the motivation. The planning behind the murders is always meticulous: the murderer knows who will be where when, how many minutes he or she has to cross the garden and enter the study window, how important it is that the poison is administered with the bedtime cocoa and not the after-dinner coffee, or how the drinks on the tray must be arranged just so in order that the victim chooses the correct one.

Of course, they make other errors which eventually lead to their downfall. Yet it is this absolute attention to detail that I believe makes Christie novels so intriguing. It’s the puzzle that’s important and puzzles can eventually be solved. All the pieces are there; the reader just has to put them together correctly – which of course we rarely, if ever, do – and that’s exactly where Christie’s genius lies.

Despite her upper-middle class background, Agatha Christie always felt like something of an outsider, which likely accounts for two of her most famous detectives, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, being on the margins of society: Poirot is a foreigner and Marple is elderly. As such, they are able to bring attention to both the idiosyncrasies and the shortcomings of English society.

But there is another way in which Christie undermines the very essence of Englishness, and, in doing so, also undercuts the stereotypes associated with it. Her books capture that beautiful feel of an orderly life: the clock ticking in the drawing room, the letters on the breakfast tray, the train arriving at exactly three minutes past four. Her characters who lead such orderly lives are well-spoken, polite and know which spoon is for the soup and which for the dessert. The undermining of all this is what unsettles us so much. How could the vicar’s wife devise a murder so clever and with such calculation that it takes the powers of a super sleuth to detect the flaws? How could the murderer have written such hateful letters in the beautiful library; how could they have thought of putting poison in the tea served so punctually at four o’clock on the terrace?

It unsettles us. Christie takes us into the dark areas of the places we consider safe. More than that, the very things that add to that lovely slow rhythm of conventionally English life - trains that run on time, tea at four o’clock, an efficient postal system - seem to have been used against us. If these things, these people, these places are unsafe, then where is not? We would feel less vulnerable on the streets of New York or in the ganglands of Glasgow. As readers, we feel we have got into the car of the stranger our parents always warned us about. But they were smiling, they were welcoming, they had double-barrelled surnames we say – and so we seal our doom.

The good thing, of course, is that she rescues us. The detective arrives, the plot is worked out and the murderer is caught. Except perhaps for Murder on the Orient Express, everything is sorted out and any loose ends are firmly tied up. The puzzle is solved and the dark places dissolve. Once again, the calm ticking of the clock is restored. That is what I find so satisfying and that is what appealed so much to my grandmother. She had come to fear life. Her experience told her that anything can be taken from you at any time, even people you love with your entire self. Being a good person, living a good life – what did it mean? It was no guarantee that you wouldn’t be dealt a terrible hand. But if the dark places were not made light in her own life, at least they were in fiction.

|

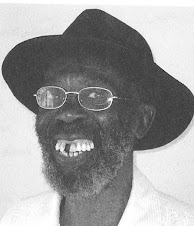

| Bryony with Matthew Pritchard |

In 2014, I was a winner of the Write Your Own Christie competition organised by AgathaChristie.com. The prize was dinner with Agatha Christie’s grandson, Matthew Pritchard, and her publisher at HarperCollins at Greenway, her home in Devon. It was an emotional moment for me, one that linked the little girl who spent afternoons listening to her grandmother’s stories of life in India and Persia to the adult with a longing to write a crime novel of her own.

|

| Outside Agatha Christie's House in Greenway |

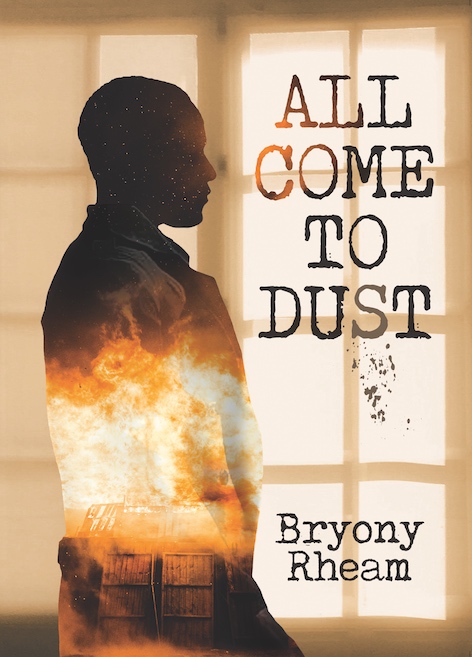

Yet it was to be another six years before this became a reality. All Come To Dust was published in Zimbabwe in November 2020, the UK in September 2021, and in the US this month. When I sat down to write it, I wanted to follow the structure of a classic Christie novel. However, there were some very obvious differences that I had to negotiate: present day Bulawayo is very different to the England that Christie wrote of from the 1920s to the 1970s. A closed murder seemed unlikely; in fact, it felt claustrophobic. The more I thought and planned, the more that it became apparent that many of the conventional tropes of the western crime novel would not work.

Zimbabwe’s police force is riddled with corruption. It is also generally quite inefficient and there would certainly be very little forensic investigation into a death. However, I still decided to use a policeman to investigate the murder. He is also an outsider, a man who wants to do good in a world that seems overwhelmingly corrupt. He spends his time typing up traffic offences, trying to put the world to rights through the meticulous recording of events that will probably be settled by the payment of a bribe to someone on the force.

The lack of forensic investigation was a bonus for me as I, like Agatha Christie, could concentrate on the puzzle and not get weighed down by having to bring in technical detail. Nor did I go into any great description of the murder itself for I do not feel the need to do so. This is probably one of the reasons why reviewers often describe All Come To Dust as ‘an old-fashioned’ murder.

Yet this would suggest a ‘happy ending’ and, while it is true, that the mystery itself is solved, there is also a strong sense that any form of justice in Zimbabwe is not administered in the conventional way. The sense of restored order evident at the end of an Agatha Christie novel is also not present. The peace is hesitant, wary, aware always that it is under threat.

|

| Modern Day Bulawayo |

I might not have set out to undermine the archetypal crime novel, but it became increasingly clear that the structure did not sit well in an African setting. It seemed obvious therefore to try and highlight this disconnect rather than ignore it. In doing so, I was able to explore modern Zimbabwean society through an eclectic range of characters, each bound in some way to the past and fearful of the future.

When I finished writing All Come To Dust, I decided that I would not write another crime novel. I had set myself a challenge and I had completed it. But now I see crime writing offers so many opportunities to explore the inconsistencies evident in Zimbabwean life. And so it is that the quest to follow Agatha Christie’s journey has led me to a journey of my own. I can only be excited of what lies ahead.

Bryony is to participate, with Michael Sears, at this year's International Agatha Christie Festival.

.jpg)

.jpg)