Zimbabwe’s Cultural Heritage (2005, amaBooks, Bulawayo) is a collection of essays on the culture of the Ndebele, Xhosa, Tonga, Shona, Kalanga, Nambya and Venda ethnic groups of Zimbabwe.

The author offers a brief historical background for each group providing the reader with a contextual framework to appreciate and understand the various cultural practices under review. According to Nyathi, in the book’s introduction, “Zimbabwe’s Cultural Heritage was born out of a desire to promote and preserve for posterity our nation’s cultural traditions.”

In the years following Zimbabwe’s independence, literature tended to sketch out grotesque images of colonial rule while also being a conveyer-belt of optimism for the better days ahead (Waiting for the Rain), the constructed history eulogising the newly born “nation”

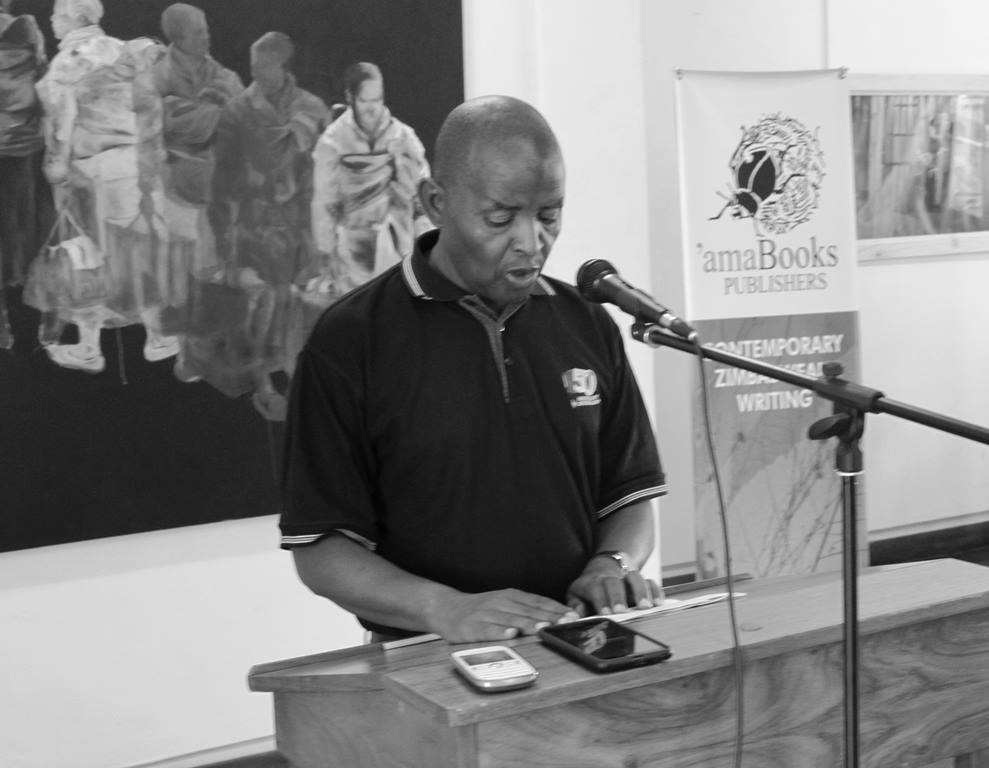

However, other writers began to express deep disgruntlement, to them all they could see was a “Long Time Coming”, rather a delayed dawn of Uhuru. In the contested terrain of identity and belonging, Pathisa Nyathi, decided to “decriminalise” the subject of ethnicity, thus validating Brilliant Mhlanga’s call for the celebration of ethnicity and not criminalising it through narrow nationalist discourses. Zimbabwe’s Cultural Heritage offers a unique contribution to the subject of belonging in Zimbabwe. It avoids both the idea that “patriotic history” should take the lead in constructing the national image, and the anti-nationalist narratives. Hence Nyathi’s work steps away from the literary norm of this time.

He states on the back cover that “the emphasis of this book is not on the histories of the groups, but on their cultural practices.” This substantiates the unique character of the text and makes it a relevant point of reference in cultural research. It is outstanding discourse compensates for the limited narratives of its kind in Zimbabwe where literature is often politicised and ethnic narratives further polarise the nation. Though Zimbabwe has a variety of cultures, it has inherited a legacy of a domineering culture, resulting in the younger generation being ignorant of their cultural roots. Nyathi’s work clearly sets out the differences and the commonalities of the cultural practices of the groups considered in the text, demonstrating that there is a “Zimbabwean Cultural Heritage”. Nyathi searches into the empirical depths of ethnic values and norms and how these define belonging and identity.

When Nyathi speaks of the Ndebele it is clear that he is an insider. Here oral tradition is still alive in the 21st century and can be used as a research method. At the same time written history validates his submissions. The language and tone is not discriminatory, it speaks to all age-groups. Nyathi’s style of inter-marrying English with local languages helps in articulating the key issues. The indigenous terms used give life to the isiNdebele, Venda, Kalanga and other groups’ practices.

There is more of an emphasis on the Ndebele than on the other groups; perhaps this is to balance their relative absence in other historical narratives of the ‘nation’. Not all ethnic and racial groups in Zimbabwe are considered in this text and one would hope for a second volume to give consideration to these.

Above all, Nyathi has shown that ethnic groups are pillars of national consciousness and that they must be celebrated in order to dismantle any leanings towards intolerance.

by Richard Runyararo Mahomva

Sunday News Online: May 8 2016

An excerpt from http://www.sundaynews.co.zw/nyathi-and-mathema-turning-to-afrocentric-paradigm-of-conceptualising-the-nation/

.jpg)

.jpg)