It seems a very long time ago that I was living in London and sharing a house with numerous other young people. In order to save money, three of us shared a bedroom, a disastrous idea for someone like me who craves privacy and space. As a result, I turned to my notebook and began to write. I recorded observations, bits of conversations, thoughts; in short, anything. I even wrote down things that happened to other people in the house as though they had happened to me.

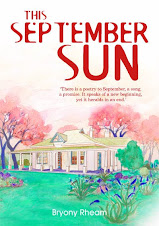

It seems incredible sometimes that these notes evolved into a manuscript and finally a book. I remember the feeling I had when I received the first copies of This September Sun, opening the box and taking the books out, not really quite believing that my dream had come true.

A lot has happened since then. This September Sun was published in the UK by Parthian and got to number one on Amazon. Two years ago, it was translated into Arabic and in 2019, it was launched at the Cairo International Book Fair. This year, I was delighted to be invited to attend.

I don’t think I have ever seen so many people buying so many books before. There are 22 million people in Cairo and every single one of them appeared to be at the Book Fair.

As soon as I arrived, I was whisked off to take part in a discussion of the book. It is always interesting to see which questions different interviewers find relevant. Here, I was asked how long it took me to write and, when I answered ‘ten years’, the next question was naturally ‘why?’ Here, I think back to my London notebook: because, until you have had something published, you are not a writer; you are just an obsessive note-taker. Moreover, the people who take you least seriously of all are your family so that whenever you need that time off by yourself to write your novel, there is a certain rolling of eyes and reference to you ‘still doing that’ as though if you had any sense, you would have given up on it years ago. My comments seem to resonate with some of the audience, particularly the women, and one lady comes up to me afterwards and says she knows exactly what I meant.

Like many authors, I shy away from classification. I don’t like being described as an African writer or a woman writer or a white writer. Leaving writing aside, I am all too aware of my rather precarious status as a Zimbabwean and feel somehow that I am out of place, sitting here talking about Zimbabwe. When I am asked, for example, if race relations have improved between white and black people, I wonder if people will believe me if I say I think they have. And when I say that the majority of white Zimbabweans want to be considered as simply Zimbabweans, I hope it rings true with the audience.

In the evening we go out for a meal. It’s crowded, hectic, chaotic. It’s the perfect place to lose all hang-ups about who you are and where you are from. From my point of view, coming from a country where no one can escape the cloud of gloom that hangs over us, it’s great to see people out and about, eating with friends and family, enjoying themselves as people should.

On the way back to the hotel, we talk about belly dancers. Sherif Bakr, from the publisher Al Arabi, says that every Egyptian girl knows how to belly dance if only in the privacy of her bedroom. Later on, just as I am falling asleep, I think about the notes I wrote in the bedroom I shared in London. I make no connection between belly dancing and writing except to say that both are an expression of our inner voice, one that needs expression somewhere, if even in the tiniest, most cramped of spaces.

The Arabic edition of This September Sun is on my shelf beside the other editions. It would be great to see it in other languages, but I am happy with where it has gone so far. Recently, I saw a picture of it at the Muscat Book Fair. I felt the pride of a parent who sees their child has grown up into an adult who knows where they want to go. It is a part of me, but no longer mine. It’s my story but it will be read by different people in different ways. I’m glad I kept a notebook.

.jpg)

.jpg)