Monday, September 28, 2009

This September Sun at Intwasa

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

'amaBooks at Fine Things from the City of Kings

’amaBooks were involved at the Fine Things from the City of Kings fair at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo We had a stand and some of the writers - John Eppel, Christopher Mlalazi, Pathisa Nyathi, Shepherd Mandhlazi, Monireh Jassat, Farai Mpofu, Linda Msebele, Mthabisi Phili, Deon Marcus and Raisedon Baya - were available to sign books and to talk to members of the public.

Fine Things from the City of Kings featured the very best of Zimbabwean art, books, craft, design, food and hospitality during the weekend of 12 September.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

This September Sun available soon

.jpg)

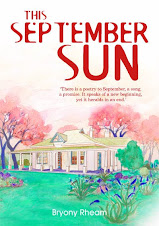

The latest 'amaBooks publication - the novel This September Sun, by Bryony Rheam, is at the printers and will be available in Zimbabwe at the end of September. It is a substantial novel, of 364 pages, and the cover design by Veena Bhana is based on a painting by Bulawayo artist Jeanette Johnson.

This September Sun is a chronicle of the lives of two women, the romantic Evelyn and her granddaughter Ellie.

Growing up in post-Independence Zimbabwe, Ellie yearns for a life beyond the confines of small town Bulawayo, a wish that eventually comes true when she moves to the United Kingdom. However, life there is not all she dreamed it to be, but it is the murder of her grandmother that eventually brings her back home and forces her to face some hard home truths through the unravelling of long-concealed family secrets.

In this absorbing debut novel, Bryony Rheam expertly combines the Epistolary, the Bildungsroman, Romance, and Mystery to produce a work worthy of a place in the bibliography of post-colonial writings in Africa. - John Eppel

Saturday, September 5, 2009

Long Time Coming Review: from The Raconteur

“2 l8 4 crisis”

To appear in The Raconteur, www.theraconteur.co.uk

Who – among Brits – gives a shit about Zim? (Hello there, Zimbabwean Raconteur readers in exile! And hello to other readers with Zimbabwean roots and ties! But apart from you…?) During the campaign to kick out white farmers, in 2000-2002, British media were full of Zimbabwe. Now we just get occasional reports about cholera, and crazy inflation figures. The latest: 231 million per cent. And unemployment: 94%. And life expectancy: 37. Zimbabwe was a rich agricultural country. Now the people are mostly starving, and violence and disease are endemic.

Up here, people protest if fuel prices rise. In Long Time Coming several stories are about travelling on overcrowded “chicken buses”, or with people who still have cars, who sell rides to the highest bidder at the roadside, to pay for fuel. Sandisile Tshuma’s autobiographical “Arrested Development” opens the book. She pays 800,000 dollars to get from Bulawayo to Beitbridge, on the South African border. First, she has to wait for a ride: “I had to wait two hours to get money from the bank to pay for my journey and now here I am waiting. Again. It’s what we do. We wait for transport, for electricity, for rain, for slow-speed internet connections […] but you know how hope is. It never dies. So we tell ourselves that there isn’t anything yet. We’ll find a way out; in the meantime let’s wait.” While waiting, she gets a text from a friend, joking that “since life expectancy in Zim is reportedly quite low, she reckons she is entitled to a mid-life crisis”. But she has miscalculated. Tshuma replies: “Sori m8. In mid-20s nw so u hav abt 10 mo yrs left 2 liv. Thz r the sunset yrs. 2 l8 4 crisis.”

I don’t have space to mention many of the good things in the book, but two extraordinary, visionary stories stand out for me: resonant visions of feminine hope and masculine horror, suggesting alternative futures. Judy Maposa, in “First Rain”, recounts a dream of a proud, naked, goddess-like woman amid torrential rainfall which cleanses Zimbabwe of its traumatic history, flushing away Gukurahundi and Murambatsiva, feeding the turbines of Kariba, bringing a rich harvest and an end to power cuts. Finally the narrator is woken by her daughter – “The taps are coughing. Get the containers” – and smiles: “Everything is going to be alright.” Here, visionary hope transcends everyday reality. By contrast, Thabisani Ndlovu’s “Stampede” recounts the nightmare of a young soldier walking for days through moribund wilderness, to and from his mother’s abandoned hut, in search of weapons he seems to have lost, to join an uprising against the regime of the “Great Leader”. The uprising is is crushed before it begins, and he joins a terrifying stampede of faceless fleeing figures, stamping soft body parts underfoot, before collapsing in a dry riverbed. Torrential rain falls, only to bring more horror: he must take off his uniform to avoid detection as a rebel, but it sticks to him wetly. His mother appears, trying to help him, but is crushed in the stampede… This story ends with a bitter laugh and the deeply ambiguous question: “Was there anyone left with the Great Leader at all?”

.jpg)

.jpg)