Saturday, October 29, 2011

YouTube video of the Bulawayo launch of Where to Now? Short Stories from Zimbabwe

John Eppel's Hatchings reviewed by Barbara Mhangami-Ruwende

The incisively satirical novel Hatchings, by John Eppel, is set in the city of Bulawayo, during the doldrum years of post independence Zimbabwe. In it we find Elizabeth Fawkes and her family, a representation of the ever dwindling middle class and middle class values of solid family ties, sound education, hard work and integrity. The story centres around the Fawkes family, who are in a sense the barometer of normality against which the reader can measure all the other characters in the novel. Some of these characters are extreme criminals of foreign extraction whose predatory instincts bring them to the chaos that is Zimbabwe and become the opportunistic parasites feeding voraciously off the dying country. Such an unsavory character we find in the person of Sobantu ‘the butcher’ Ikheroti, who is devoid of conscience or anything that amounts to human sympathy. Ikheroti is involved in the business of providing illegal abortions to pregnant underage girls, who have been put in the family way, thanks to the rampant penchant for “Black pussy”, by two British expatriate primary school teachers, Simon and Nicholas. Enter the Ogojas, Nigerians, who deal illicitly in stolen emeralds and who are in business with Ikheroti, who incidentally pimps the girls he provides abortions for so that they can pay him back for relieving them of their unwanted babies. The dead babies are passed on to the esteemed artist Ingeborg Ficker, who is creating an organic statue using hills valleys and trees called the Gwanda Giantess who will be birthing these babies.

Eppel’s characters move along the natural continuum of class and racial composition of Bulawayo (and therefore Zimbabwe), sardonically invoking stereotypes of the various classes and racial groups. There are the residents of Cornwall Street in the city centre: the Amazambane and the Ilithanga families, Ndebeles who cohabit in one small flat, all 14 of them. There is the old coloured family, the Reeboks, whose one son was hanged for murder, the other was doing time and the mother of their 11 year old granddaughters was strung out on drugs. The bitter divorcee, Aphrodite Fawkes, and the bachelor Boland Lipp, in possession of pathetically good heart and a love for classical music and the colour green, complete the residents on Cornwall Street. Let us not forget the Indian landlord who is reminded of the plight that befell his kinsmen in Uganda when he inquires about the number of people living in flat 3- the Ndebele flat.

Enter the Mashitas - the Shonas, who have turned their whole yard into a maize and vegetable farm, the Macimbis - the Ndebeles, who have assisted nature by denuding their yard of all vegetation and swept the ground clean of its topsoil, the Voerwords of Afrikaans ancestry and the Pigges, whose lineage hails out of England. All of them are neighbours to the Fawkes family and their children, Black and white play in the neutral zone which is the Fawkes’ backyard. They are in what was formerly a middle class neighborhood but the clear delineations that defined such a neighbourhood have become somewhat blurred.

Then we move on into the world of the obscenely rich, those who can afford to waste water in a city whose resources are fast dwindling. It is the world of the born again Christians with their ostentatiously wealthy pastor whose powerful preaching of the gospel of prosperity induces mind numbing orgasms to the women folk in the congregation. It is the world of true believers who sing and dance and clap and in trancelike state sign huge cheques for the Lord. It is from this world that the Black Rhino elite private school draws its student population with the sole aim of “ensuring the high standards of Rhodesian education”. At this school, the students, over indulged children of the wealthiest farmers and business men excelled in those aspects of Rhodesian education which mattered the most: “rugby, water polo, bullying and geography”. In this setting we find the very ordinary Boland Lipp as the English literature teacher who strives to impart a love for the written word to his students, who are only really interested in brand new fast cars, motor cycles and sex.

In stark contrast to Black Rhino School is Prince Charming High School, embedded in one of the ghetto townships of Bulawayo. It is here that Simon and Nicholas the English teachers teach politics and have sex with the female students, getting a fair number of them pregnant, which results in expulsions and several fair skinned babies found dumped in different places around the city.

John Eppel sets the scene for New Year’s Eve parties in the city of Bulawayo, by providing imaginative and hilarious descriptions of the idiosyncrasies of each of his characters. Each character, community, race and class brings a different but colourful dimension and meaning to the terms corruption, greed, slovenliness, debauchery and selfishness, which renders the story of the parties on New Year ’s Eve in the various locations uproarious. Despite the dead babies that are a constantly being discovered throughout this story, Eppel succeeds in delivering a story about a city whose inhabitants have lost the qualities of Ubunthu: those qualities which form the fabric of strong communities in which the individuals care about the wellbeing of the others, demonstrated in simple acts such as preserving water during a drought, in order that there may be enough for everyone. This delivery is neither moralistic nor judgemental, but it is brutally honest, stripping individuals literally to their bare bottoms and institutions to reveal their rotten innards, all accomplished with humour, great skill and unparalleled precision.

The story lifts the reader out of the filth and one is deposited at a light, hope inspiring end. Young Elizabeth Fawkes’ love for the ruthlessly handsome, devil- may- care Jet Bunion is finally reciprocated, and the egg she has been incubating for her father in her bra is hatching. Fresh beginnings and a new day are possible after all.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Conversations with Writers: Barbara Mhangami-Ruwende

One of her short stories has been featured in Where to Now? Short Stories from Zimbabwe (amaBooks, 2011).

In this interview, Barbara Mhangami-Ruwende talks about her concerns as a writer:

Do you write every day?

No. I do not write every day. That is in part due to time constraints but also because I spend a lot of time reading or creating stories in my head so that when I do sit down to write, I write as opposed to thinking.

I am putting together a short story collection and working on a novel.

I create stories while I am chopping vegetables or folding laundry. Then when I have half an hour to sit at my computer, it is to put down something. The writing usually ends because I have something to attend to, like the pot of burning stew!

Often times I have a notebook close by to jot ideas down as I go about my daily activities, including grocery shopping.

What are the biggest challenges that you face?

So far the biggest challenge I face is juggling family life and finding the time to write. My daughters are 10, 8 and 5 (twins) and they require a lot of energy and attention, which leaves very little time for much else.

I have learnt to be extremely efficient in my use of the little time that I do have.

When did you start writing?

I started writing and enjoying it when I was in Grade 7. I was about 12 years old.

Over the years I have written creatively and, also, as a scientist. Currently, I write literary fiction. Short stories mainly.

When I started writing seriously last year, I was doing it mainly for my friends who I went to school with and those who knew me growing up. Over the years many of them have suggested that I write and so I started a blog purely to share stories with friends and family. My friend, Sarah Ladipo Manyika, who I have known for 10 years, read some of my pieces and hooked me up with a couple of editors of literary journals and the journey began.

My most significant achievement as a writer has been to turn a personal passion into something to be shared as a way to entertain and perhaps to enrich others. This, above all else, gives me the greatest satisfaction.

My only hope is that whoever gets to read my stories enjoys them as much as I enjoy writing them. My hope is also that my stories appeal to those who are familiar with the environment and the experiences that inspire the stories as well as to those who enjoy a good, well-written story no matter what the story's context or background.

How have your personal experiences influenced your writing?

My personal experiences have an impact on my writing in many ways. I recognize that my prose style borrows heavily on the oral, story-telling tradition that was very much a part of my childhood. My experiences living in the village provide a rich context for many of my stories.

My extensive travels and living in different countries has shaped many of my views and beliefs and this comes through in some of the characters I create, as does personal loss and challenges that I have had to face.

Being a wife and a mother also feed my writing tremendously.

Which authors influenced you most?

I draw inspiration from many writers from different backgrounds and eras. The ones that come to mind, because I read them over and over again, are: George Orwell, for his crisp uncluttered style; Milan Kundera, for his audacious and oftentimes crazy characters; Toni Morrison, for her uncanny ability to revisit the same subject matter and present it in unique ways through compelling characters and use of language; Chinua Achebe, for telling a story that would have an indelible impact on my young psyche as an African teenager in a predominantly white school; Tsitsi Dangarembga, for weaving an amazing tapestry in which I could locate myself as a Zimbabwean woman, in her book, Nervous Conditions.

There are so many more writers who have influenced my work and my desire to write and share my stories: Chris Mlalazi, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Charles Mungoshi, John Eppel, Amos Tutuola, Wole Soyinka, Ama Ata Aidoo, Yvonne Vera and so on and so forth.

What are your main concerns as a writer?

My one major concern is the fact that there seems to be an expectation that as a writer who is Zimbabwean and therefore African, I cannot create art for art’s or write for writing’s sake. There seems to be this expectation that as a writer I have the responsibility of being a good ambassador for country and for continent.

What concerns me is the definition of good ambassador. Who is articulating it and the parameters that are used to define the 'good ambassador'? I live in angst over the fact that I may be accused of pandering to the west by presenting an Africa that fuels their hunger for sad stories of war, boy soldiers, famine, poverty and corruption. It seems that this is quite an issue based on the criticisms that have been leveled against contemporary writers whose work I identify with.

http://conversationswithwriters.blogspot.com/2011/10/interview-barbara-mhangami-ruwende.html

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Where to Now? reviewed on www.mazwi.com

Reviewed by Drew Shaw

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Murenga Joseph Chikowero interviewed on Conversations with Writers

Zimbabwean writer, Murenga Joseph Chikowero is a doctoral student in African Literature and Film at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In 2010, he collaborated with Annie Holmes and Peter Orner on an oral history project which gave birth to the highly-regarded book, Hope Deferred (McSweeney’s Publishing, 2010).

His short stories have featured in the anthology, Where to Now? Short Stories from Zimbabwe (amaBooks, 2011) as well as on the PanAfrican writers’ blog, StoryTime.

In this interview, Murenga Chikowero talks about his concerns as a writer:

When did you start writing?

Back in primary school, probably in 6th grade.

That year, I moved to a different part of the country, near Guruve in the north, and there a friend told me a story, one of those fantastic tales. When I went back to my old school a year later, our teacher asked everyone to write a story, any fictional story. I wrote down this story about a mythical, one-eyed giant but ... when our books were returned ... mine wasn’t there! Our teacher had misplaced it. When she eventually found it, she asked everybody to stop whatever they were doing to listen to my story.

That, for me, was when writing stories down began although storytelling itself was nothing new in my family and, indeed, other families in the villages.

How would you describe your writing?

I write mainly short stories though I have a novel on the way.

I am fascinated by the 1980s, the time when so many people felt they could dream ... independence was finally here and, for that reason, young men walked with a pronounced swagger, shirts unbuttoned down to the navel and hats worn at fancy angles. Young women wore their over-ironed pleated costumes, stretched out their graceful necks and went about their business. My writing traces the radical and more subtle changes from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe and what ‘Zimbabwe’ meant to different generations and groups. The clamor of the post-2000 politics masks the amazing beauty – and. yes, largely untold trauma – of the 80s and I try to recapture that in my fiction.

Outside fictional writing, I recently collaborated with two writers, Annie Holmes and Peter Orner on an oral history project that gave birth to a book called Hope Deferred. That project basically attempts to bring voices of ordinary Zimbabweans – at home and abroad – to bear on the narrative of Zimbabwean crisis of the last decade. I traveled to Zimbabwe and interviewed some of these witnesses and victims of torture and political persecution.

Hope Deferred is a collection of some of the most remarkable personal stories of ordinary people’s experiences of state-sponsored terrorism, their struggles for a better society and, ultimately, the triumph of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

My short fiction generally targets a mature audience but my novel-in-progress courts younger Zimbabweans although all English speakers will find something to enjoy there too. A lot of our young people today have no clue what the 80s and 90s meant – or promised – to those who lived through them. The beauty and ugliness of that period is unlike anything we have seen since.

In the writing you are doing, which authors influenced you most?

Because my school didn’t have a library, I read whatever I found.

The adolescent detective genre was quite an obsession early on, especially the American variety: the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew series. Nothing was better than lying on my back before the yellow light of a paraffin lamp after supper and join Frank and Joe Hardy and their friends – and sometimes their father Fenton – as they put together the puzzle pieces of some big crime in their town.

Then, after reading No Longer at Ease, I considered myself a firm disciple of Chinua Achebe. No book made me happier even with its subtle, controlled prose. Achebe’s fiction, though written in English, read like my native Shona and I liked that instant recognition.

I bumped onto a battered copy of House of Hunger by Dambudzo Marechera in between reading the then ubiquitous Pacesetter series that we exchanged in middle school and I was instantly hooked. The problem, though, was that the copy was so battered it had no cover so there was no way of knowing its title or author.

But the Pacesetters series! My very first Pacesetter was called Evbu My Love by a Nigerian writer named Helen Obviagele. It was a somewhat sad story but there was something about love brewed in the African pot that nibbled gently at your heart and made you read the story once, then twice.

The Pacesetter Series was impressive for its vivid language and fast-paced action by African heroes and, occasionally, heroines. Secret service heroes like Benny Kamba in Equatorial Assignment. Some of the heroes had English names such as Jack Ebony in Mark of the Cobra but that didn’t bother us and we were right there with him as he delivered deadly karate kicks to venomous snakes hidden in his wardrobe by enemies of the state.

I also read some South African fiction, most of which I didn’t particularly like at the time, perhaps because the first ever South African novel I read was Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country. The Pacesetters had introduced me to African heroes who could punch their way out of trouble so I found Cry, the Beloved Country particularly depressing.

Luckily, Dambudzo Marechera saved me around this time. A friend let me borrow his House of Hunger though we didn’t find out what the title was until much later. Unlike anything I had read before, Marechera seized me by the scruff of my neck and thrust me into a violent yet fascinating world of the ghetto slum. I had not stayed in any urban ghetto so the world of House of Hunger shocked me. Another happy problem was the language; I didn’t understand a lot of the more flowery prose but it excited and shocked me in equal measure. A less happy problem was that Marechera, of course, didn’t see anything wrong with describing graphic sexual acts, sometimes even in our native language and so I got a bigger book, a schoolbook actually, planted House of Hunger right in the middle and read and re-read the numbing details of ghetto life while my teachers marveled at my keen academic interest!

Around the same time, we discovered James Hadley-Chase, Louis L’Amour and the British classics – usually the abridged versions.

My older brothers also read anything under the sun and kept personal libraries of sorts. I was allowed to read these books – as long as I was behaving myself. I liked history books the most because they were packed with biographies of larger than life characters, characters who rose from nobodies and turned the world upside down. I liked all of those legendary figures. Our government was then heavy on what is called Gutsaruzhinji or Socialism and there were all these history books detailing the Chinese Revolution of 1947. I would look at a certain picture of a youthful Mao Zedong – then called Mao Tse Tung – and envy his army cap.

My brothers also had collections of Shona language novels, some of which were course setbooks at school. I detested the moralistic variety churned by the sackful by our Literature Bureau but absolutely loved the detective thrillers like James Kawara’s Sajeni Chimedza and Edward Kaugare‘s Kukurukura Hunge Wapotswa. Though targeted at older readers, these novels were not too different from the Pacesetter Series. Above all, I loved the Shona language liberation war novels, the best of which was Kuda Muhondo by a writer whose name I forget. The more overtly partisan ones like Zvairwadza Vasara, I didn’t particularly like.

These books and experiences shaped my early writing and made me feel I could try my hand too.

What are your main concerns as a writer?

Each time I sit down to write down a story, I am always struck by James Baldwin’s assertion that the job of the writer is to look for the question that the answer tries to hide. And yet we often think of the answer itself as a solution to a query.

The ease with which myth passes off as truth in Zimbabwe motivates me to write fiction. My major concern is the place of historical memory in contemporary Zimbabwe. A lot has happened and we have a state that considers it a moral obligation to control this narrative, especially since the year 2000, thanks to a severely – and perhaps deliberately – stunted media landscape. I use different generational voices to interrogate these changes that have happened.

For example, one of the biggest myths in our country is that all Zimbabweans lived happy, comfortable lives before the Mugabe-led farm takeovers which began in earnest around 2000. Few people are honest enough to remember that the ruling elites, led by Mugabe himself, actually colluded with the rich white farmers and industrialists to lord it over an impoverished population.

Who remembers now that the farm takeovers were actually planned and spearheaded by ordinary villagers? Who remembers that these villagers were actually arrested for their efforts before political expediency made it necessary for our politicians to turn round and celebrate these villagers as heroes of the Third Chimurenga? I try to write beautiful stories that bring a more nuanced understanding to these issues.

What are the biggest challenges that you face?

The biggest challenge facing most Zimbabwean writers today is the shrinking publishing industry. This, of course is true throughout Africa with South Africa as a possible exception.

The few, mostly independent publishing houses left in Zimbabwe are forced to put their few resources behind book projects by trusted names so as to recoup their investments. Yes, ours is still a society that views fictional writing as something of an indulgence, a hobby for the educated class. Of course, there is that basic question: Who is going to buy a book when all the money they have can hardly buy a loaf of bread?

You will notice that, contrary to the 20 years leading up to 2000, there are fewer fresh writers whose works are published individually. The tendency has been to produce these anthologies from which some talented voices occasionally emerge, for example, both Brian Chikwava and Petinah Gappah published short stories as part of this short story anthology tradition before launching individual careers as celebrated writers. To date, I have also pursued a somewhat similar path although some of my stories have been published in the form of e-books in South Africa.

Do you write everyday?

Because I balance an academic career with writing fiction, I cannot write everyday. It is also not my style to write everyday. I generally let a story or a chapter ferment in my imagination for days, rather like chikokiyana, our traditional brew, before writing it down. But when I start writing, the story demands that I finish it in one sitting, much like a gourd of frothy chikokiyana. Then I pass it on to my partner to read. She is by far my harshest critic so I usually listen to her opinion before editing my stories.

Ever since I discovered Dambudzo Marechera, Toni Morrison, Njabulo Ndebele, V. S. Naipaul, Charles Mungoshi, Joseph Heller and Ernest Hemingway, I have never liked a story whose conclusion is overwritten, especially if it’s a short story.

My short stories in particular use plenty of silences which estimate real-life African dialogue as I have experienced it.

I have a special dislike for stories that end in formulaic ways ... for example, a relationship that ends with a wedding or a rogue who is caught and jailed. I like my rogues out there, maybe some of them reform or they are chased out of town but I like them better out there and not in jail. Instead of a wedding, I am usually satisfied with lovers looking into each other’s eyes or even doing seemingly small things for each other.

My most recently published short stories include “The Hero”, which was featured in an anthology called Where to Now? Short Stories from Zimbabwe by amaBooks, a Bulawayo-based publisher. I have also published two stories, “When the King of Sungura Died” and “Uncle Jeffrey” on the PanAfrican writers' blog, StoryTime, which is managed and edited by Zimbabwean-born writer, Ivor Hartmann.

How would you describe "The Hero"?

“The Hero” is about an accidental hero who starts off as a rather banal political party thug who falls into a large beer container at a party rally and dies. His party declares him a hero and on the day of burial, he even dislodges the president from the news headlines. "The Hero" is based on a true story that happened in Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe, around 2003.

I wrote it in one sitting, as I usually do with my short stories, and it was published in Where to Now? by Bulawayo-based amaBooks in 2011. My story speaks to other stories in that anthology, all by fellow Zimbabweans. In my story, for example, the ill-fated character is essentially a victim of an economy gone haywire; he takes to partisan politics like one possessed. In NoViolet Bulawayo’s award-winning story in the same volume, “Hitting Budapest”, you find a similar theme of ghetto kids craving for very basic necessities of life which their parents cannot provide, thanks to a crashed economy.

The ghetto setting is something I am very familiar with. I think a story’s power also draws from its ability to evoke a setting that readers recognize.

Which aspects of the work did you enjoy most?

Creating the ghetto scene and the atmosphere of a Zimbabwean political rally are the two things that I enjoyed most. Political rallies in Zimbabwe have a whole life of their own.

I also especially liked working with Jane Morris, the editor of Where to Now?.

What sets "The Hero" apart from other things you’ve written?

The satire ... Some of the so-called heroes and heroines buried at our publicly-funded heroes’ burial sites – heroes’ acres as we call them, including the National Heroes Acre, are no heroes at all ... But because of media censorship, there is little public debate about these kinds of issues outside the columns of the few privately-owned newspapers ... Thankfully, developments in Information Communication Technology have seen a steady rise in online newspapers, blogs and online social forums where a culture of robust debate is slowly taking root.

What “The Hero” shares with my other stories is the fascination with Zimbabwe’s public memory, particularly how it has been edited, suppressed and manipulated at various times to suit the goals of the political class.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Where to Now? reviewed in Newsday

Where to Now? — Short Stories from Zimbabwe

REVIEWED BY CYNTHIA R MATONHODZE - Oct 11 2011 06:43

Editor: Jane Morris

Publisher: ‘amaBooks, Bulawayo, 2011, 146pp

The anthology Where to Now? Short Stories from Zimbabwe features a mixture of 16 Zimbabwean writers, some new and others well known, among them 2011 Caine Prize winner NoViolet Bulawayo and 2011 World Summit Youth Awards runner-up Fungai Rufaro Machirori.

Published by ‘amaBooks, it is the fifth book in a series of short story writings the first being Short Writings from Bulawayo (2003)* and the most recent one Long Time Coming: Short Writings from Zimbabwe (2008).

Where to Now? casts autobiographical tales of life and living in Zimbabwe’s lost decade when the economy crumbled, inflation reached dizzy heights, violence replaced the rule of law and most people fled the country.

What is autobiographical about these stories is different Zimbabwean authors delivering narratives that speak of events, phases, characters and images that are conspicuously Zimbabwean, creating a lingering reflection which prompts the reader to ask: Where to now? From the black purchasing manager who struggles with whether or not he is a true African — when a fellow colleague accuses him of being a sell-out for eating isitshwala with a fork and knife and only using the company fuel allocation he needs in Mzana Mthimkhulu’s I am an African, am I? to the couple that goes to the UK, each assuming another identity, to work and send money home to build their dream house only to be swindled by a relative who had been sending them pictures of someone else’s house in Blessing Musariri’s Sudden Death — each story tickles the memory to recall that period and sometimes even crafts out a memory that will have you sad, in stitches, inspired, disillusioned or even questioning yourself.

For example, Raisedon Baya’s Her Skin is a Map and Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s Crossroads, both writers tell the story of migrating to South Africa. One traces the events that lead most to leave while the other sketches out the tedious humiliating process many Zimbabweans went through for the promise of a better life, only to have that hope shattered by reality. Etched in these tales are themes such as violence, corruption, family disintegration, desperation, hope and disillusionment. Baya uses nature and the park to lament and trace the deterioration of human relationships in society, in Zimbabwe.

“The park has changed. The grass is no longer entwined together like lovers. The grass is gone, replaced by an angry gold that attacks the eyes. The trees look unhappy, betrayed. If they could walk they would have left the park a long time ago.” (p56). Now, “The people that come to the park now are not lovers with spirits, they are not families that want a day out, but unemployed people who are hungry and tired of hunting for jobs and are here to rest and hide from prying eyes,” (p58).

Baya remembers happier times where as a little boy they would have a picnic in the park at Christmas with his family, everything joyous with the promise of independence. Now when he takes his own family to the park they end up being badly beaten up by riot police who suspect that they are striking teachers. Then and there he makes up his mind to leave with his family for Durban.

Tshuma creates a vivid image of the process of migrating in a young woman’s journey from Zimbabwe to South Africa in the hope of getting a job and saving up enough money for university. In Zimbabwe – no water, no electricity (depending on where you stay), a never-ending queue at the South African Embassy with enterprising individuals that sell their positions in the queue.

At the border — never ending queues, rude and indifferent immigration officers, stories of having been robbed in South Africa and the public toilets that read:

Toilet paper only

To be used in this toilet

No cardboard

No cloth

No Zim dollars

No newspaper p (69)

Baya and Tshuma clearly and skillfully capture memories of that sad period in Zimbabwe’s history, painfully personal for most. There are some lighter stories like Mapfumo Clement Chihota’s A Beast and a Jete which is a story within stories of clever women that out smart their husbands.

Other stories include themes such as xenophobia, poverty, marriage, lost hope, infidelity, love, misplaced hate, the new generation of women, a dishevelled society, loneliness, the pain of remembering, death, coming home, the born-frees, political machinations, life in limbo and black and white relations.

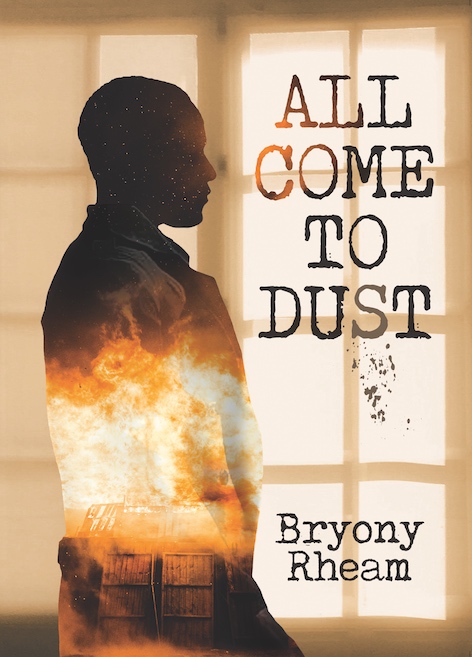

Other contributors include Barbara Mhangani-Ruwende, Thabisani Ndlovu, Bryony Rheam, Nyevero Muza, Christopher Mlalazi, Diana Charsley, Murenga Joseph Chikowero, John Eppel and Sandisile Tshuma.

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Owen Maseko, from NoViolet blogs

be causing trouble—like,

undermining the authority

of the president, like

brushes and colors in hand,

he be painting truth, making truth, like,

shedding dark blood, digging old skulls

unburying the murdered, imagine that,

like giving them bright-red voices,

after all these years - almost 30 solid,

saying their names, hanging the dead

on a clothesline for all to see,

like nobody didn’t teach him - didn't tell him

Zim is a land of silent silence,

where they edit expression on final cut pro

with police whips and guns and prisons

people living hand to mouth,

famished for rights, for freedom,

for the sound of their own true voices

see us walk like zombies in Zim, like

paralyzed by fear of the state in Zim

we could flee our shadows in Zim,

we see nothing, we hear nothing in Zim

let them silence us, beat us in Zim, like

what does freedom matter in Zim?, like

we have Owen Maseko to show, right

now here’s staring at a blank cell

reading the writing on the wall

scribbled in blood, left hand too,

“Jestina Mukoko was here” like

we have Gukurahundi to show

we have murambatsvina to show

we have persecuted whites to show

we have the 2008 election to show

but you can’t ask us nothing coz

we won’t say nothing, but like,

in our dreams though, we roar with rage,

wave bloodied shirts in the wind,

wave Gukurahundi skulls and femurs,

we knock down prisons, like, we throw

rocks at police, we gut jails, like,

we protest until they free Owen Maseko,

in our dreams we are almost brave, and

the president is an old man who fears our power. © NVB

Where to Now? reviewed on www.examiner.com

Where to Now? Short Stories from Zimbabwe

Edited by: Jane Morris

Reviewed by Rosetta Codling

European Literary Scene Examiner, www.examiner.com

October 6, 2011

Synopsis: This work is a collection of complex, human dramas focusing upon the realities of Zimbabwean and African life. The writer Mzana Mthimkhulu contributes to this collection an intriguing question and excerpt entitled I am an Africa, am I? This African-Cartesian question is not easily answered in this short story. Mark, a colleague of Timothy, the protagonist, raises this question to his friend. Mark’s query resonates throughout the selection. Timothy is a successful man. He adheres to the guidelines in his Western workplace. In doing so, is he betraying something? Tradition vs. Modernity is the conflict…here…and always in Africa.

Blessing Musariri’s contribution entitled Sudden Death is a ‘brief’ about trust and kinship. The hopes and dreams of several women in the story become entwined upon a literal ‘cross’ borne by one man. Was it wrong to place such a burden of trust upon a person? Was it foolish not to assume that repercussions would occur?

The selection The Piano Tuner, by Bryony Rheam, stirs the reader’s imagination. The main character, Leonard Mwale, is a Zambian piano tuner by trade. He goes to luxurious homes and tunes things into shape. Many patrons send a car for him and offer him a free meal in addition to his fee. For, Leonard Mwale is a skillful man. Tragic are the many ailments in the household that he services in this selection.

In summary, there are no ‘nicely constructed’ plots or storylines in this collection. However, the readings will challenge your imagination and your concept of ‘self.’

Critique: This is the best collection of short stories from Jane Morris so far! I did enjoy the stories and the complex plots. The African literary tradition is illustrated and represented well by these writers and stories. This is a collection for every lover of African literature. Educators and sociologists take note and get a copy!

.jpg)

.jpg)