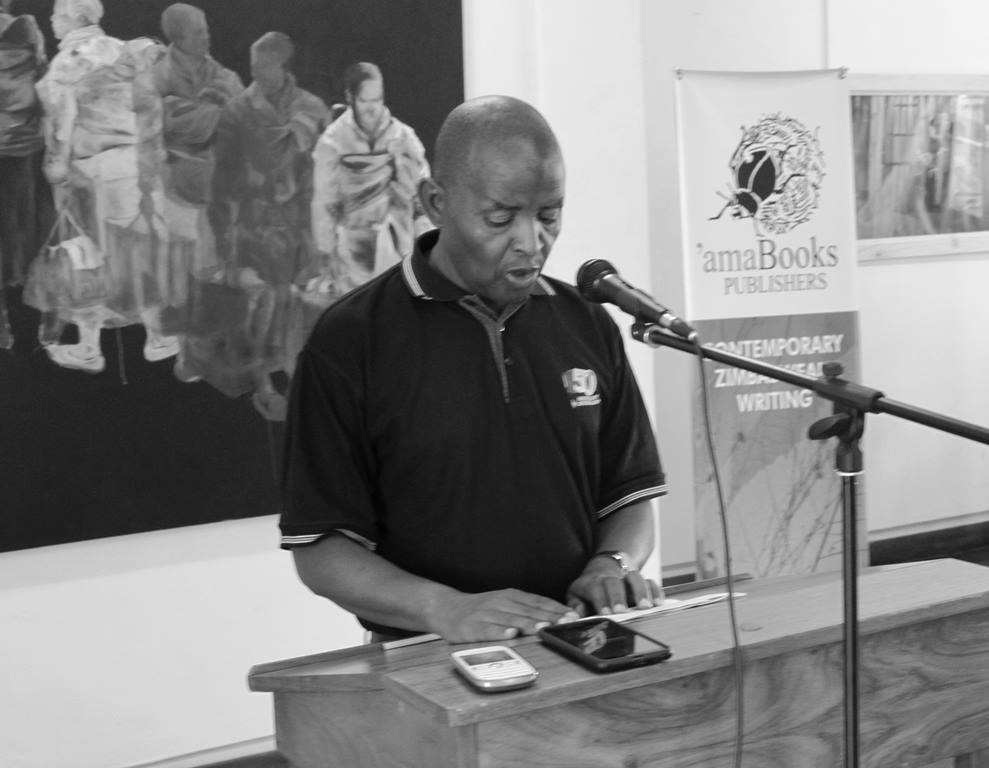

Lusaka Punk and Other Stories, the 2015 Caine Prize for African Writing anthology, has been published in Zimbabwe by 'amaBooks. It is available in Bulawayo from the National Gallery, Induna Arts, Orange Elephant and Book and Bean, and in Harare from the National Gallery, Avondale Bookshop and from Weaver Press.

Now entering its sixteenth year, the Caine Prize for African Writing is Africa's leading literary prize, and is awarded to a short story by an African writer published in English, whether in Africa or elsewhere. This collection brings together eighteen short stories - the five 2015 shortlisted stories, along with stories written at the 2015 Caine Prize Writers' Workshop that took place in Ghana.

Previous collections have showcased young writers who have gone on to publish successful novels, including NoViolet Bulawayo, Leila Aboulela, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Sefi Atta, Brian Chikwava and Helon Habila.

'amaBooks have also published previous Caine Prize anthologies in Zimbabwe, and recently published The Maestro, The Magistrate and The Mathematician, the second novel by Tendai Huchu, who was shortlisted for last year's prize.

This year's winner of the prize is Zambia's Namwali Serpell, for her short story 'The Sack'. The other shortlisted writers included Segun Afolabi (Nigeria), Caine Prize winner in 2005; Elnathan John (Nigeria), who was shortlisted in 2013; F. T. Kola (South Africa) and Masande Ntshanga (South Africa). The 2015 Caine Prize workshop participants included Diane Awerbuck (South Africa) and Efemia Chela (Zambia/Ghana) who were shortlisted for the 2014 prize, Onipede Hollist (Sierra Leona) who was shortlisted in 2013, and nine other promising writers: Dalle Abraham (Kenya), Nkiacha Atemnkeng (Cameroon), Akwaeke Emezi (Nigeria), Timothy Kiprop Kimutai (Kenya), Jonathan Mbuna (Malawi), and Jonathan Dotse, Jemila Abdulai, Aisha Nelson and Nana Nyarko Boateng (Ghana). The facilitators at this year's workshop were Leila Aboulela and Zukiswa Wanner.

Chair of judges Zoë Wicomb described the shortlist as ''an exciting crop of well-crafted stories... Unforgettable characters, drawn with insight and humour, inhabit works ranging from classical story structures to a haunting, enigmatic narrative that challenges the conventions of the genre.''

She added, ''Understatement and the unspoken prevail: hints of an orphan's identity bring poignant understanding of his world; the reader is slowly and expertly guided to awareness of a narrator's blindness; there is delicate allusion to homosexual love; a disfigured human body is encountered in relation to adolescent escapades; a nameless wife's insecurities barely mask her understanding of injustice; and, we are given a flash of insight into dark passions that rise out of a surreal resistance culture. Above all, these stories speak of the pleasure of reading fiction.''

.jpg)

.jpg)