Saturday, July 30, 2011

Where to Now? The South African Launch

Sunday, July 24, 2011

'Where to Now?' at ZIBF 2011

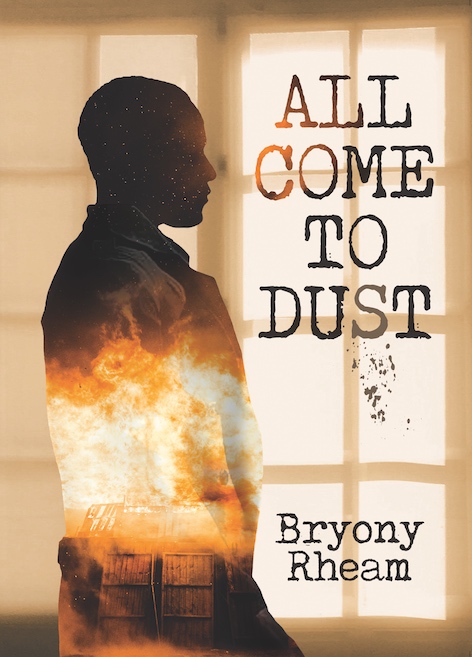

’amaBooks will introduce their latest book to the public during the Zimbabwe International Book Fair 2011, which takes place at Harare Gardens from 28 to 30 July. The collection, Where to Now? Short Stories from Zimbabwe, features sixteen Zimbabwean writers - Raisedon Baya, NoViolet Bulawayo, Diana Charsley, Mapfumo Clement Chihota, Murenga Joseph Chikowero, John Eppel, Fungai Rufaro Machirori, Barbara Mhangami-Ruwende, Christopher Mlalazi, Mzana Mthimkhulu, Blessing Musariri, Nyevero Muza, Thabisani Ndlovu, Bryony Rheam, Novuyo Rosa Tshuma and Sandisile Tshuma.

The writing in this collection, at times dark, at times laced with comedy, is set against the backdrop of Zimbabwe’s ‘lost decade’ of rampant inflation, violence, economic collapse and the flight of many of its citizens. Its people are left to ponder – where to now?

All the voices are Zimbabwean. Even though some speak from the diaspora, their inspiration comes from their homeland and their stories tell of Zimbabwe.

In the pages of Where to Now? you will meet the prostitute who gets the better of her brothers when they try to marry her off, the wife who is absolved of the charge of adultery, the hero who drowns in a bowser of cheap beer and the poetry slammer who does not get to perform his final poem. And many more.

The book is the fifth book in the award-winning ’amaBooks Short Writings series, the most recent being Long Time Coming: Short Writings from Zimbabwe, chosen by New Internationalist as one of their two ‘Best Books of 2009’. The short story and poetry collection Together, by John Eppel and the late Julius Chingono, was launched in Bulawayo in June, and this book will also be featured on the ’amaBooks stand at ZIBF 2011.

Where to Now? is being co-published with Parthian Books and the book will be available in the United Kingdom in March 2012. Parthian will launch the book together with Bryony Rheam’s debut novel This September Sun, published by ’amaBooks in 2009.

2011 is the first time that ’amaBooks have had a stand at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair in Harare and they look forward to meeting the readers and writers of the capital.

A Caine Prize Diary, by Tolu Ogunlesi

A Caine Prize diary

July 23, 2011 06:41AM http://234next.com/csp/cms/sites/Next/ArtsandCulture/Books/5734779-147/story.csp |

An intimately-laid-out setting awaited me when I walked into the 17th centuryOld Schools Quadrangle of Oxford's Bodleian Library, on Monday July 11, for the 2011 Caine Prize dinner. There were fourteen numbered tables, each seating eight or so persons, and all buzzing with small talk until prize administrator, Nick Elam mounted the podium. Kadija George, publisher and literary activist, was seated next to me. Having known and corresponded with her by email for six years - in 2005 she published a selection of my poems in her litmag, Sable - it was a pleasure to finally meet her.

To my right sat Ann Driver, who introduced me to her husband, C.J., poet, novelist, and 2007 Caine Prize judge. "A hundred years ago I taught Jon Cook [Emeritus Professor of Literature at the University of East Anglia] at school," he joked.

As one would expect of Britain's most high profile prize for writing by persons of African origin, the guest list was impressive. Ben Okri, Alastair Niven, Becky Ayebia-Clarke, James Gibbs, Kaye Whiteman, Aminatta Forna (a judge this year), Elleke Boehmer, Ellah Allfrey, Leila Aboulela (the inaugural Caine Prize winner), Maya Jaggi, Mohammed Kabir Umar, Richard Dowden. I spotted Cassava Republic publishers Bibi Bakare and Jeremy Weate near the front of the hall.

Changing of the guard

Jonathan Taylor, Chair of the Caine Prize Council, gave an opening speech, highlighting the "recognition, reward and readership" that the Caine Prize had brought to African writers. He announced that Elam, who has overseen the prize since its launch in 2000, would be stepping down in August (he will take up the role of company secretary), to be replaced by Lizzy Attree.At intervals novelist and poet Nii Ayikwei Parkes read from the shortlisted stories. For anyone used to awards ceremonies in Nigeria, this was a marvellously unfussy gathering; the speeches were brief, and the waiters brisk.

Baroness Nicholson of Winterbourne, President of the council, noted that the annual Caine fiction workshops (there have been nine in the 12-year history of the prize) formed the "core" of the prize's growth. She paid tribute to Nick Elam's efforts atmanaging the prize and the workshops, and announced that Ben Okri had agreed to be Vice President of the Council.

At a few minutes past 10pm, the Chair of the Board of Judges, Libyan novelist Hisham Matar, announced Zimbabwean NoViolet Bulawayo as the winner of this year's prize, for her story, ‘Hitting Budapest' (published in the November/December 2010 edition of The Boston Review), about a starving yet boisterous gang of children on a guava-hunting quest in a rich neighbourhood. "This is a story with moral power and weight, it has the artistry to refrain from moral commentary. NoViolet Bulawayo is a writer who takes delight in language," Matar said.

The first tweet

Shortly before then I had typed out the twitter message I was going to send, announcing the winner. As soon as Bulawayo was announced I inserted her name in the space I had left for it in my tweet, and sent the message. (The following day in London one of the PR people told me my tweet was the first announcement of the prize to leave the dinner venue).

Bulawayo gave a short speech, and then the photographs and interviews - and closing glasses of wine - followed.

The following day the five shortlisted writers - Bulawayo, Beatrice Lamwaka (Uganda), Tim Keegan (South Africa), Lauri Kubuitsile (Botswana) and David Medalie (South Africa) -gathered at the British Museum in London for a panel discussion. They answered questions from panel chair, Mpalive Msiska, and the audience, on the usual writerly themes: literary influences, inspiration for the shortlisted stories, experiences with editors and publishers, national and continental identity, etc.

While most of the writers traced their earliest literary experiences to reading, Bulawayo said hers came mostly from listening - to the night-time stories of her childhood in Zimbabwe.

Historian Tim Keegan said he was drawn tofiction by the "limiting methodology of history" - the strictures of footnotes and academic references. "History really leads to fiction. There's no dividing line, I think they meld into each other."

On representation

Inevitably, the issue of representation - how Africa is being portrayed in the fiction of its writers - and stereotyping came up. Since this year's shortlist was announced a debate - mostly critical - has been going on, on internet forums, about how the selections of the Caine Prize judges are shaping (distorting?) the image of Africa. For one it is hard to miss the fact that, for some reason, the winning stories in 2009 (‘Waiting'), 2010 (‘Stickfighting Days') and2011 (‘Hitting Budapest') all feature poverty-stricken children living in slums or refugee camps.

One of the loudest of the critical voices has been NEXT columnist, Ikhide Ikheloa. In May, shortly after the 2011 shortlist was released, he described it as a "humourless, tasteless canvas of shiftless Stepin Fetchit suffering." Of Bulawayo, the eventual winner, he said: "She sure can write; unfortunately, her muse insists on sniffing around Africa's sewers."

This raises the question: are writers to be judged on the subjects and themes of their writing, or simply the quality? Should a writer be taken to task for choosing "Africa's sewers" - which are all too real anyway - as inspiration for her storytelling?

Bulawayo put forward a convincing defence, arguing that there are different Africas, and no one should prescribe for any writer what Africa they ought to write about. "I am that barefooted kid who went to steal guavas," she said. That, she said, was the Africa she knew and she was under no obligation to write about an Africa unfamiliar to her.

That declaration, one imagines, should serve as an invitation to all who feel, quite strongly, that the stories of the Africa they know are not being written. If there is an imbalance of stories out there, surely the blame should go to those who should be writing but aren't, not to those who are.

In conclusion

I've come to realise that there will never be an end to all those debates - around "authenticity", "identity", "stereotyping" and "audience" - that follow writers of African origin wherever they go. African writers will forever carry the burdens of having to comment, not merely about their "Africanness" as individuals, but also about the Africanness of their writing.

"I am from Zimbabwe, yes, but this is not necessarily a Zimbabwean story; it can happen to children anywhere," Bulawayo said in an interview, shortly after winning the Caine Prize. A few days before that interview appeared, last year's winner, Olufemi Terry, in an essay that appeared online in Granta, declared: "There is, for me, no African writing, only good writing and bad writing."

I agree with Terry, at least for now, until another eloquent answer emerges to the vexed question of "African Writing". I'm also starting to wonder if it wouldn't be better to drop the "African" in the Caine Prize name, and redefine it simply as "The Caine Prize for Writing" -and this without altering the eligibility requirements ("African writers").

There must be a reason why, the Orange Prize insists on referring to itself as the "Orange Prize for Fiction", not the Orange Prize for "Women's" Fiction - even though only female writers are eligible. That it celebrates writing by women should not be interpreted to mean that there is such a literary category as "women's writing" - unless the increasingly ridiculous V.S. Naipaul is to be believed.

In that stance may lie a lesson for the Caine Prize.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

The John Eppel (Together) Interview, with Rosetta Codling

From: http://www.examiner.com/european-literary-scene-in-national/the-john-eppel-together-interview

*Fascinating note: John Eppel is the author of Hatchings (2006), White Man Crawling (2007), Absent: The English Teacher (2009), and other works. He is a poet, novelist, short story writer, and teacher. He resides in his beloved homeland Zimbabwe. The latest contribution of Eppel to the literary scene is a joint endeavor, Together, with his deceased kinsman Julius Chingono. John Eppel presents a work that permits the reader to gain a glimpse into the unique, political, literary artistry of two famed writers.

Question: What is the symbolic meaning behind the title of your latest work Together (2011)?

Answer: It is unusual to think of an abstract word as a symbol, but when it becomes the title of a joint collection of poems and stories by a black person and a white person who spent half their lives in colonial Rhodesia and half their lives in Independent Zimbabwe, it becomes clear. Our country has been, and still is, defined by race. It’s the trump card in the game of politics. It gave rise to the word, apartheid, the opposite of which is togetherness.

Question: What brought you together with your kinsman Julius Chingono? After all, Chingono was a Black Zimbabwean and you are a White Zimbabwean, is that not so?

Answer: Neither of us was part of the mainstream, Nationalism, which dominated Zimbabwean writing in the first twenty years of Independence. I for obvious reasons, and Chingono because, as the late Lionel Abrahams put it in his postscript to Chingono’s poetry collection, Flag of Rags:

For all his special power of compassionate empathy with other people, his altruism, Chingono is his own man. In contrast to much protest and political poetry, his art does not spring out of a collective Cause or big Idea. Everything he writes rings of personal knowledge and experience, his own individual thought. He never trots out the fashionable formula, the convenient stereotype, the party line.

The fact that we were both marginalized for so many years was one reason for bringing us together. Another, I believe, is that, long before we met, I wrote a positive review of his poetry (in the defunct Southern African Review), which he appreciated. A third and most important reason is that neither of us judge[d] people by the colour of their skin but by their behaviour.

Question: Does your vocation as an English teacher trespass… or overlap upon your vocation as a writer?

Answer: Both. It trespasses in the sense that it leaves me little time to write; it overlaps in the sense that it provides me with much of my material, especially in my prose writing.

Question: As a writer, you are a member of an aesthetic community, why trespass into a political arena in your work?

Answer: Consciously apolitical writers are just as political as consciously political writers. The decision not to vote in an election is a political act. I like what Theodor Adorno says about this: “A work of art that is committed, strips the magic from a work of art that is content to be a fetish, an idle pastime for those who would like to sleep through the deluge that threatens them in an apoliticism that is in fact deeply political.”

I also believe that writing, especially poetry, should be beautiful, crafted. That’s where form comes in.

Question: How were you called to write…poetry…short stories….novels?

Answer: This is a difficult one. In my case, I think it might be a substitute for religion. The aesthetic experience, what James Joyce called an “epiphany”, seems to be a secular version of the religious experience. It’s got a lot to do with mortality.

Question: What does Together (2011) unfold to the reader that your previous works have not?

Answer: It is much more overtly political; there is less white guilt… that’s about all.

Question: Sick at Heart is a very emotional poem that defies nationality. How did you come to write it?

Answer: The year 2008 was Zimbabwe’s annus horribilis. The economy collapsed totally. People’s pensions and life savings were reduced to nothing. A mass exodus took place, mainly to South Africa. School teachers like me were earning less than a dollar (US) a day. It was also an election year, which resulted in the brutal deaths of over 200 opposition supporters. My story, “Of the Fist”, which records one of these deaths, was edited out of Together because the publishers found it too shocking. “Sick at Heart” was allowed to remain because it is metaphorical. The title (and the last words of the poem) comes from Hamlet. To this hour there is something rotten in the state of Zimbabwe. Not one of the perpetrators of those rapes, tortures and murders has been brought to book.

Question: Can you provide us with some ‘insider’ details about your selection entitled English Sonnet in Broken Metre?

Answer: As I have said elsewhere, I don’t write sonnets, I write parodies of sonnets. My seeming fixation on prosody is a deliberate form of self-mockery, an accusation of the culture that produced it. This poem is an angry response to the way some western governments baled out obscenely rich brokers with public money. One of the paradoxes of capitalism is the richer you get the cheaper living becomes. In Zimbabwe, as the final couplet suggests, it’s not brokers but very senior government officials who regard public funds as pocket money for themselves.

Question: What is the dramatic and political irony of your short story Who Will Guard the Guards?

Answer: One of the ironies here is that there is a strong perception in Zimbabwe that whites are fair game when it comes to the “redistribution of wealth”. The reasoning is that the whites, historically, took everything from the blacks, so why shouldn’t the blacks, now, take everything from the whites? If you go far enough back in history, say 2 000 years, you find that that the Shona peoples were also settlers in this part of the world, and they would have been the first to displace the aboriginal San peoples. I guess the distance you go back in history is determined by political expediency.

Our so-called guards – the police, the army, the CIO – are partisan, and that is a very scary situation for anybody who is not a paid-up member of ZANU-PF.

Question: Your short story The Debate sheds light on international, political hypocrisy. How did you come to write this powerful treatise?

Answer: The cartoonist in me.

Question: The death of the legendary Julius Chingono calls upon us all to think of our legacies. What will your legacy be?

Answer: A rickety old house (if it doesn’t get redistributed), a 1978 Ford Escort, the complete recordings of Enrico Caruso, and a fistful of poems.

The Crisis Of Creativity And Creativity In The Crisis: What Is The Point Of Books In Zimbabwe?

From: http://africanarguments.org

July 15, 2011

In the wake of celebrations that once again a Zimbabwean author, NoViolet Bulawayo, has won the Caine Prize for African Writing, a revived Zimbabwe International Book Fair (ZIBF) will be taking place in Harare at the end of July (25th-30th). The theme of the Book Fair will be ‘Books for Africa’s Development’. Last week, a well-attended event at the Book Café in Harare debated the past and future for the ZIBF, and ended up discussing the question, ‘what is the point of books in contemporary Zimbabwe?’ The theme of this year’s ZIBF gives some clues as to dominant thinking on the answer: books are for development. But what do books contribute to development, and how will books in Zimbabwe help to ensure that ‘things can only get better’?

A striking feature of the event at the Book Café was the contrast between the two speakers in how they conceptualised what ‘running’ the ZIBF entailed. Roger Stringer, describing the early years of the ZIBF up to 2000, gave a detailed account of the challenging logistics of organising a major international trade fair – particularly during a period of strict exchange controls and particularly one that, unlike most international book fairs, also invited the public to come in and buy books. Musa Zimunya, who chairs the current ZIBF Association and was covering the years since 2000, did not discuss ZIBF as an organisational challenge and gave no detailed analysis of the specific reasons for the collapse of the book fair at the end of the 2000s. He spoke rather about writers as stakeholders in the book industry and the uses of literacy. His presentation was a mesmerising meditation on what it is to be writer in contemporary Zimbabwe; but not what it is to organise a book fair.

What, then, is the purpose of a Book Fair in Zimbabwe? Is to talk about books? Or to sell rights to publish them? One of the innovations of the early years of ZIBF had been the ‘Indaba’ – a registration-only programme of conferences and seminars running alongside the commercial trade fair and the public open days. The Indabas covered topics such as ‘Gender, Books & Development’, ‘Human Rights’, and ‘Promoting Tolerance and Dialogue’, where publishers could stimulate public interest in the issues covered by their literature. The Indaba was useful in engaging the general public and brought in a range of players (notably academics, NGOs and CSOs) that might not otherwise have become engaged. Now, however, the ‘Indaba’ seems to be the main event of the Book Fair, rather than a parallel event to bring in participants. As Zimunya noted, ‘There was no book fair in 2008 and 2009, leaving local writers to run the Indaba as a day’s affair’. Roger Stringer has pointed out on the ZIBF Facebook page, ‘You can see from this how it has become much more a “conference” and much less a “trade fair”’.[1] It is also noticeable that the event is now seen as belonging to writers, rather than to publishers.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the ZIBF was the premier book fair for all book deals within Africa – not only between Southern African publishers and the rest of the world, but also between publishers within Africa itself. At last week’s meeting, Stringer stated that he does not think that it can ever regain that status – not because other states have stepped in to fill the vacuum that was created during Zimbabwe’s ‘difficult decade’ of the 2000s, but because big trade fairs have been made obsolete by technological change. Publishers no longer need to meet in person in order to have conference meetings, to exchange contracts or to look at proofs. All of these things can be done electronically, via Skype and pdf documents emailed between negotiators. There is some truth to this observation. However, Frankfurt Book Fair is still as vibrant as ever, suggesting that publishers do still feel the need to gather together in a trade fair setting.

Indeed, the need for African publishers to attend international trade fairs was indicated by a recent report from Bulawayo-based ’amaBooks on their experiences at the 2011 London Book Fair. Brian Jones of ’amaBooks observed that:

A major activity at the fair is the selling of rights amongst publishers. When, for example, a United Kingdom publisher agrees to publish a book by an author, the contract usually involves the publisher acquiring world-wide exclusive rights for that book. But the publisher is not usually in the best position to promote and arrange distribution of the book everywhere, so will try to sell the rights for a particular market, say North America, to a publisher based there…The scale of these rights sales at London can be appreciated by one floor of Earl’s Court being dedicated to rights negotiations. [2]

For African-based publishers, it is important to be able to contact other publishers and negotiate the rights to allow their books to be published and marketed elsewhere in the world. Particularly for publishers with low international visibility (ie the majority of African publishing houses), the opportunity to meet a large variety of potential partners and make a face-to-face impact is essential. The case for a large and effective trade-oriented book fair within the African continent seems clear. But there was little evidence that the current organisation of the ZIBF is oriented towards such an event.

Nonetheless, Stinger’s point about technological change was quickly picked by other commentators. One speaker suggested that the ‘moment of the book’ had passed; soon it would be obsolete. But Zimunya spoke lyrically about the vital importance of books in rural communities with negligible internet access, where development projects depended upon a textual support, and where more literate members of the community could easily share the material with others. Books, qua object, have practical benefits over all other forms of communicating information. And, as Brian Jones commented, ‘In London there were iPads and Kindles all over, but they are still are a rare sight in Zimbabwe and I don’t foresee printed books disappearing from Zimbabwe anytime soon.’

But, as publisher Murray McCartney, of Weaver Press, pointed out, the nature of the platform is, in any case, irrelevant. A book is a book regardless of whether it is delivered by a screen or by a page. A more pressing question is what writing is for. The problem in Zimbabwe is not that books are dying out as objects made of paper, but that they are dying out as a genre.

Zimbabweans display a changed attitude towards reading, after their hard decade. It is strange now to recall the days in the 1980s when Dambudzo Marechera sat in Africa Unity Square day after day, writing obsessively and magnificently, and insisting that those around him engage with ‘difficult’ prose. Reading still takes place, of course: this is, after all, the most literate nation in Africa.[3] Newspapers are read avidly; twitter feeds clutter Zimbabwe’s cyberspace; Wikipedia provides a quick fix of information. But reading is not given time. Even in the world of literature, short stories, such as NoViolet Bulawayo’s Caine Prize-winning ‘Hitting Budapest’, predominate over novels.

The crisis of books is seen everywhere. Bookshops are hard to find; and when you do find them, they disappoint. An African film-maker based in Kuwadzana, a high density suburb just outside Harare, told me that he used to enjoy reading contemporary fiction and works on film criticism, which he could find in Kingston’s, the state-owned bookshop and stationers. Indeed, a visit to Kingston’s was once rated in the top 40 things to do in Harare by Lonely Planet travellers.[4] But now, he said, ‘There are no books; and if there are any there, they are just text books and manuals funded by NGOs.’

This point was reiterated by Irene Staunton of Weaver Press at the ZIBF event at the Book Café (a café, incidentally, that was once a book shop with a café attached, but where now, as Eugene Ulman, who made an influential film about the café, commented: ‘You’d be hard pressed to find a book at the Book Café’). Staunton pointed out that publishers are struggling because people no longer expect to pay for books. Books are conceptualised as something that NGOs provide for free, to schools, communities and project participants, as part of a ‘package’ with an instrumentalist purpose. Books are for training, not for leisure. And they are certainly not for enhancing a society’s imagination.

At every turn, an instrumentalist attitude to books and reading predominates. The novelist Zimunya’s robust and moving defence of the importance of books in rural areas was describing the importance of training manuals, not of novels. Meanwhile, at the University of Zimbabwe, the world’s academic journals are freely available to the undergraduates, thanks to gratis subscriptions to JSTOR and to the journals of significant publishers such as Cambridge University Press and Taylor and Francis. Africa Journals Online provides three free downloads per month to anyone accessing their pages with a Zimbabwe-based IP address.[5] And yet, university lecturers complain to me that their students are simply not making use of collections such as JSTOR, even when the technical support would allow them to do so. Undergraduates – and even some teaching staff – tend to seek affirmation from canonical texts rather than to engage with a wide range of positions. Reading tends to be focused on data mining rather than tracing the development of ideas and the conversations between academics. A revolution in resource availability has not led to a revolution in academic engagement or the blossoming of ideas.

Despite the high literacy rates, people no longer seem to love books in Zimbabwe. One publisher told me that, ‘Parents don’t read to their children any more. Children encounter books at school and those experiences with books are often bad ones.’ And, she added, in a culture that is highly oriented towards kinship, community and patronage networks, community activities are valued above the solitary and individual act of reading. Undoubtedly, the avid – often social – reading of newspapers, along with the urban ubiquity of social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, maintain a text-oriented and literate culture. But book-reading is in decline.

It seems that an educational system that encourages conformity in learning, combined with an economy now largely dominated by NGO interventions, has reduced books to tools in learning. At the Book Café, Murray McCartney made an impassioned plea for a re-valuing of creativity and the contribution that literature makes to the imagination. There were important questions implicit in his words. Without a culture of creativity, where will writers and publishers find a new vision for the ZIBF? How will Zimbabweans come up with creative solutions to climb out of the economic pit of the past decade? But no-one in the gathering picked up his call.

Diana Jeater

[1] https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=180642298667093&id=29744297362

[2] Brian Jones, ‘’amaBooks Goes to the London Book Fair’, zimbojam.com, 9th June 2011, http://www.zimbojam.com/culture/literary-news/2705-amabooks-goes-to-the-london-book-fair.html

[3] UNDP Human Development Report 2010, The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2010/

[4] http://www.lonelyplanet.com/zimbabwe/harare/things-to-do. See also Kudzai Bare, ‘Creditors Stalk Kingstons’, Financial Gazette (Harare), 13th August 2010.

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

Bulawayo writer wins 2011 Caine Prize

NoViolet Bulawayo wins 'African Booker'

(From http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/jul/12/noviolet-bulawayo-caine-prize)

£10,000 Caine prize goes to story by Bulawayo writer

Zimbabwean author NoViolet Bulawayo has won major African literary award, the Caine prize, for her short story about a starving gang of children from a shanty town.

Bulawayo's Hitting Budapest tells the story of six children in Zimbabwe, one of them pregnant with her grandfather's baby, and the journey they make to steal guavas in a rich area. Chair of the Caine prize's judges, the Libyan novelist Hisham Matar, said the story's language "crackles".

"Right now I'd die for guavas, or anything for that matter. My stomach feels like somebody just took a shovel and dug everything out," writes Bulawayo. "Getting out of Paradise is not so hard since the mothers are busy with hair and talk. They just glance at us when we file past and then look away. We don't have to worry about the men under the jacaranda either since their eyes never lift from the draughts. Only the little kids see us and want to follow, but Bastard just wallops the naked one at the front with a fist on his big head and they all turn back."

Matar said the gang in the story – Darling, Bastard, Chipo, Godknows, Stina and Sbho – was "reminiscent of Clockwork Orange. But these are children, poor and violated and hungry". He praised Bulawayo's "moral power and weight", and her "artistry to refrain from moral commentary", saying that she "is a writer who takes delight in language".

Born and raised in Zimbabwe, Bulawayo has just completed her MFA at Cornell University in America, where she now teaches. "The story came from this need to engage with the world," she said this morning. "I'm interested in what happens when two different worlds meet in a problematic way, I'm interested in honesty and in violence. These are real issues and real things."

Although her character Darling longs to live in America, and Bulawayo has lived in the US since 1999, the country "does not feel like home", the author said. "I miss home. I want to go and write from home. It's a place which inspires me. I don't feel inspired by America at all," she said.

The Zimbabwean writer was "excited" to win the Caine prize, which is worth £10,000 and known as the African Booker, counting Wole Soyinka, Nadine Gordimer and JM Coetzee among its patrons. "It's one of Africa's biggest literary prizes," she said. Bulawayo has just completed a novel, tentatively entitled We Need New Names, which "explores some of the same themes as the story", and is working on a memoir, but has yet to find either a literary agent or a publisher. "I hope somebody finds the manuscript worthwhile," she said. Previous winners of the Caine prize include Zimbabwean Brian Chikwava, Sudan's Leila Aboulela and Nigerian writer Helon Habila, all of whom now have book deals.

Gothataone Moeng interviewed by Emmanuel Sigauke

Your story “Who Knows What Tomorrow Brings,” published in Long Time Coming ('amaBooks 2008) looks at the unpredictability of change, how so suddenly Zimbabweans who used to be welcomed with smiles in Botswana are now being spat at, now labeled thieves and evil herbalists. In writing this story about the misfortunes that had befallen Zimbabwe, were you devising a social justice statement? In fact, this seems to be one of the preoccupations of most of your stories, whether you are writing about the role of children in society, the importance of women in patriarchal societies, and the issues of gender and sexuality in general: do you believe it is the role of fiction to deal with such issues?

This question is very difficult to answer because I have actually been asking myself the same question, of whether as a writer I should write fiction that deals with social issues. I do think that fiction has a role to at least make readers aware of such issues, but what I have noticed with a number of Batswana writers (I myself have fallen prey to this) is that this responsibility or need to talk about issues often ends up as a sort of burden. The message then becomes the point of the story and the story becomes quite didactic. We have thus had a deluge of stories about HIV that are very predictable, a variation of the Joe comes to town story, where a young innocent girl comes from the villages to the city, and is soon caught up in the fast paced Gaborone life and disregards advice from friends and family, etc. and then falls sick. My own solution to this is that I don’t make the issue the focal point of the story; I make the character the focal point and then explore how such a character navigates their way around such an issue. I do sometimes write stories that do not deal with any serious issues, but none of these have been published, so maybe it’s also a question of what people want to read.

For the complete interview with Gothataone, please visit

http://storiesonstagesacramento.wordpress.com/2011/06/22/emmanuel-sigauke-interviews-sos-june-featured-author-gothataone-moeng/

Saturday, July 9, 2011

Zimbabwe's literary kinsmen: Together, part II

Together: Stories and Poems, 2011,

Genres: Poetry and short stories

Literary Elements: Imagery, wit

Comfort Level: Easy reading….but attention to detail is advised

Synopsis: The reader will find that John Eppel’s political side is unleashed ‘sans’ the covert references noted in his novel Absent:The English Teacher (2009). Together is about the fraternity of two political writers. Julius Chingono’s works are showcased in the early portion of the collection. John Eppel’s works follow. The poems of John Eppel entitled ‘The Coming of the Rains’ and ‘Charles Dickens Visits Bulawayo’ stem from the vast literary repertoire of the English teacher. Eppel can summon Rousseau, Kafka, and Dickens in a manner that facilitates the reader’s ability to implement ‘relevancy’ as a means of contrasting and comparing past political issues with those occurring in contemporary Zimbabwe. The author’s methodological (*classic John Dewey style) skills, as an English teacher, surface here. The short story ‘Who Will Guard the Guards’ is quite universal in the message illustrated. Eppel fashions an honorable, White, Zimbabwean character (perhaps) filled with guilt for the past colonial atrocities suffered by his Black kinsmen. The White Zimbabwean displays enough compassion and empathy to provide residency for a needy kinsman. But, the ‘needy’ man responds to the noble gesture in classic socio-pathetic fashion. The compassionate character goes on to find that ‘no good deed goes unpunished.’ And the new keepers of justice are as corrupted as those of the past. Is this all a form of reparations for past victims or mere revelations for the new victims? The reader must judge this one alone. The last poetry selection in Eppel’s segment ‘Waiting’ calls upon the reader to look back to Juilius Chingono’s own short story ‘We Waited’. In both selections, the writers Eppel and Chingono look and wait for change. The reader sees that these men are definitely of a similar, literary and political thread. Each man waits and beckons change in his writings. But will change come soon…or too late?

Critique: It was a pleasure to read this treasure. John Eppel continues to educate his students and readers. He is able to master the genres of poetry and short story writing with ease. This is no small feat. The works in Together appeal to the ‘literary’ scholarly set and those politically in tune with today’s events. Each segment of Together is a joy to read and savor. I do look forward to future works from John Eppel. We need brave writers to remind us of our obligations as citizens… and humanitarians, universally.

From: John Eppel is Together (II) - National European Literary Scene | Examiner.com http://www.examiner.com/european-literary-scene-in-national/john-eppel-is-together-ii-review#ixzz1RaMnokGU

Reviewed by Dr Rosetta Codling

.jpg)

.jpg)