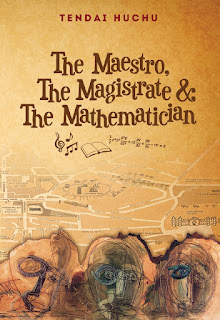

Tendai’s The Maestro, The Magistrate & The

Mathematician is not a book one starts reading and then discards. It is

also not a book just riddled with beautiful lines and expressions. Simple in

language and easy to comprehend, in what seems a full representation of

Zimbabweans in the diaspora, Tendai Huchu, himself a diasporan, takes it upon

himself to talk of Zimbabweans far away from home. The Magistrate, a man

clearly in love with his roots and desirous of home, relives the experiences of

his country by listening to its musicians, he finds himself walking through the

streets and modernity of Edinburgh with Zimbabwe booming in his ears. Tendai,

in an unflinching and unsentimental way, makes us realise the power of losing

power and importance. The anchor this book holds on to is the capacity to make

the characters friends with the reader. The most distinctive character being

the Maestro. The most comedic, Alfonso. It is difficult to find something wrong

to pin on this book.

One should not be

deceived by the title of the book and restrict the book to three characters.

There is a ring of more characters around these three Ms and it is these other

characters that Tendai uses to create a Zimbabwean community. Remove the three

Ms from the book and all the talk about Sungura music and Zimbabwean

traditional musicians, as well as the long walks and descriptions of the roads

of Edinburgh, are simply page fillers and nothing else.

The Magistrate, The

Maestro and The Mathematician are apt representations of the lives of

immigrants, especially African immigrants and the challenges and changes they

face. Most importantly it highlights the common denomination that all

immigrants face: survival. And when life is a matter of survival, nothing is

too low to do, including coming as high as being a magistrate to going as low

as ‘wiping bums’. But it is in the Maestro that we find the questions that many

fear to ask themselves, what is life all about? Thinking becomes almost a

fearful thing, and to quote the Maestro, ‘once you started thinking for

yourself, you were lost.’

Too much thinking is

sometimes associated with too much walking, going round and round just as the

person thinks more and more. And this, Tendai exemplifies well in the many walks

and morning jogging the Maestro engages in. A sort of abandon in one’s self

comes up and the world all of a sudden becomes a tiring place in which to be

and loneliness becomes a craving. The-world-should-leave-me-alone attitude is

developed and people are pushed away, sometimes with the hope that one person

won’t give up on you. And when it gets worse, a sort of comprehension of the

unknown is sought, and answers are looked for everywhere. This is the perfect

representation of the Maestro, and this character, though seeming unimportant

in the whole weave of the story, plays that important role of representing lost

immigrants who find companionship in themselves, and later on in death.

‘At work, he was

friendly, exuding something resembling warmth, but outside of work he kept to

himself. There was something safe in the white pages of a book,’ this, in

reference to the Maestro, can’t be captured better, but it doesn’t end there

because even ‘his running was a solitary thing; he did not want to be part of

the herd. It was a way of tapping into himself, which meant the discovery of

his own limits at a time when he was beginning to accept the idea of his own

mortality.’ Tendai further strengthens the depth of this character by

introducing to us the works the Maestro reads; works that are a peep into his

consistent questioning mind. First the Maestro misses work, three days in a

row, something he’d never done in four years. Then ‘the arbitrary division of

time into seconds, hours, weeks, months and seasons’ becomes meaningless. The

disposal of his furniture and television and eventually the burning of his

books, the one thing he treasures. This is the turning point.

It is the way Tendai

works out the gradual decomposition of the mind of the Maestro, from a sane

looking man, to a man whose thoughts are scary and complex and questioning, to

a man who runs away from his past and into a mind not his own that makes one

wonder what strange thoughts might be going through the minds of those close to

us.

The Maestro is a

representation of the philosophical and intellectual part of this book despite

him being an O’level certificate holder; whereas, the Mathematician, a PhD

student, whom we’d probably expect more intellectuality from, displays hedonism.

Tendai made his book a collection of contradictions.

Tendai’s Three Ms

might not jolt you out of your chair, but it will definitely leave you laughing

and contemplative.

Reviewer: Socrates Mbamaluhttp://www.olisa.tv/2016/05/21/on-tendai-huchus-the-maestro-the-magistrate-and-the-mathematician-a-peep-into-an-existentialists-mind/

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment