ImageNations: Promoting African Literature

Today, I bring you an interview (a

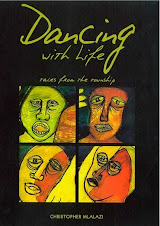

discussion) with Tendai Huchu. I interviewed him when his first book The

Hairdresser of Harare came out. He has published his second book: The Maestro,

The Magistrate & The Mathematician. I caught up with him via Facebook and

this is what ensued.

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: So how did The

Hairdresser of Harare do? And how was it accepted in Zimbabwe noting the

subject matter?

Tendai Huchu: The Hairdresser isn't a book

I think much about now. I have moved on as an artist. It was well received in

Zim. First print run sold out. Good reviews. It was a popular read.

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: OK. Great. I'm

surprised you say you think not much about it. Is it that you are more

concerned with your new work?

Tendai Huchu: Yeah, I am doing newer and,

hopefully, more interesting stuff. I have/am evolving. For me, the next project

is always more exciting than the last. I imagine it is the same for all

writers.

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: Yes. You always have

to focus on your current project and allow the last one to live its own life.

Your second book fascinates me. I was wondering what will be contained in its

pages. What's this book about?

Tendai Huchu: It is hard for me to distill

a 90,000 word text into a soundbite, particularly when it has no real central

theme. But the stuff that interested me most in making the text was the formal

stuff, mechanical things to do with structure, and, of course, playing with

genre and also trying to create a work that was ambiguous and contradictory.

This makes little sense if you have not yet read the book, but I hope you will

one day.

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: This sounds

appetising. I'm no stranger to stranger literature. In fact experimental

literature is itself novel. So will you consider your text experimental?

Tendai Huchu: I wouldn't necessarily

consider myself an experimental novelist. I don't think I wield the necessary

pyrotechnics to assume such a designation, rather the form the text was created

try to buttress the ideas in the story I was putting forward. For example, the

text contains 3 novellas, and this was only because my initial attempts at

creating a unified, conventional novel failed, and the only way I could get the

three characters to work was by highlighting their differences. It was a

process of simplification, but that comes with its own complications, the

language and style of the separate stories then had to be altered radically,

the visual presentation of the text on the page itself had to be looked into.

If there is any innovation in the text, it is merely a response to difficulties

I encountered in writing the damned thing.

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: Your response piques

my interest. After all, it is in adversity that we innovate. Your response

reminds me of Doreen Baingana's linked stories Tropical Fish. You said earlier

that the story (like Murakami's novel Kafka on the Shore) has no central theme

how then were you able to sustain the writing to reach a meaningful conclusion?

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: Your response piques

my interest. After all, it is in adversity that we innovate. Your response

reminds me of Doreen Baingana's linked stories Tropical Fish. You said earlier

that the story (like Murakami's novel Kafka on the Shore) has no central theme

how then were you able to sustain the writing to reach a meaningful conclusion?

Tendai Huchu: The conclusion is part of the

play with ambiguity that I had going on. So for long stretches of the novel you

have these disparate elements in play, but then at the denouement the camera

zooms out and you see how these events come together and have been

orchestrated, but only once you step out of the limited, chaotic experience of

the individual characters. You also come to realise that the real hero of the

story is someone else. I am talking round the book here because I am avoiding

spoilers, but the idea is that whatever position the text takes must be

undermined by an equal and opposite truth. Thus, I now do a U-turn and advance

the argument that the book actually has a theme and is tightly plotted. It is

not a literary novel but a genre novel of a very specific kind.

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: This sounds

interesting and I look forward to reading it one day. However, how's

distribution of your books like? Getting books distributed in Africa is

difficult*.

Tendai Huchu: It is published in Zimbabwe

by amaBooks and in Nigeria by Farafina. The problems of book distribution in

Africa are well documented, but we are really talking simple market forces here,

nothing more. It's not as though there are hordes of readers demanding my work

across the continent. My publishers will be lucky if they so much as break even

with this book. That's the harsh reality. Why would a publisher anywhere else

in Africa try to sell my book when they already have a hard time selling works

by their own local authors? I sound pessimistic and for this I apologise but

the future of the book industry is intimately linked to the future of the

general economy. You put more money in people's pockets and they have more

leisure time, they might indulge and engage with this art form. The state has

the resources to build libraries and stock them, there is another market for

publishers. Combine this with mass literacy and the industry has a shot. We

have to be realistic and tie the future of this art form to inescapable power

of capitalism. Books are just another product of that system. Nothing more,

nothing less.

Nana Fredua-Agyeman: Thanks Tendai for this

discussion.

_____________________

*Conducted this interview before I got a

copy of this book. My copy is published by Farafina and the Writers Project of

Ghana has copies for sale.

The book is also available in the UK

through Parthian Books and in North America through Ohio University Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)