THERE are moments when Zimbabwe’s creative spirit refuses to be contained; instants when its words, colours and rhythms transcend borders, languages, and the limits of genre.

The past two weeks offered two such moments.

These are the launch of “The Mad”, Ignatius Mabasa’s English translation of his 1999 Shona classic “Mapenzi” in Harare on October 10, and the opening of “Nzwisa”, the debut solo exhibition by bilingual writer and painter Samantha Rumbidzai Vazhure, a week later.

Though different in medium, with Mabasa’s in the printed word and Vazhure’s in textured acrylic, both events celebrate the same thing. It is the unrelenting will of Zimbabwean artists to speak in their own voices, on their own terms, and to the world at large.

The artists insist that literature and art are not parallel roads but intersecting paths in the ongoing conversation about identity, collective memory, and belonging.

When Mabasa stood before the audience at the launch of “The Mad” book lovers knew that he was not simply introducing a translation. He was introducing a movement.

For a man who did his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis at Rhodes University, South Africa, in Shona to “decolonise knowledge” and let it “speak to the people,” the translation of “Mapenzi”, his audacious, surrealist exploration of post-independence disillusionment, into English is not a retreat from that principle.

Rather, it is its extension.

Mabasa began writing “Mapenzi” as a student at 22, during the radical ferment of the 1990s at the University of Zimbabwe. Those were the years of radicalism, when students dared to dream of a freer world and writers sought new idioms.

The novel’s title, “The Mad” captured that spirit. It is a kind of madness that equates to rebellion—madness as muse, madness as resistance, and madness as truth-telling.

It reflects on how mental illness, though sensitive and serious an issue, emerges beyond affliction to become a metaphor within the imaginative and often anarchic world of artistic expression.

For both spectacle and insight, artists, especially modernists, like Mabasa, find something almost seductively resonant in the idea of losing one’s mind.

Madness, in the creative consciousness, is not simply a breakdown of the rational self. It is a way of seeing, an alternative mode of perception that unveils hidden truths.

It offers the artist a lens through which to dissect a diseased society, peel back the veneer of order, and expose the chaos bubbling beneath. In this light, madness is not a condition but a commentary.

As critic Kizito Muchemwa (2002) puts it, “Sanity is a very strange commodity in the fictional world created by the new generation of storytellers.”

This strangeness is rooted in the dissonance between the polished appearance of modern life and its deeper, more fractured reality. To speak truthfully about the human condition today, its loneliness, alienation, and existential disillusionment, artists often turn to madness, both as a theme and a symbolic tool.

Modernists are obsessed with fracture, loss, and dislocation. Their worlds are dream-like, fragmented, sometimes terrifying, and often riddled with the psychic debris of failed utopias.

In Zimbabwean literature, this obsession is profoundly felt. Writers like Memory Chirere, Ignatius Mabasa, Shimmer Chinodya, Clement Chihota, Robert Muponde, Stanley Mupfudza, and Brian Chikwava, among others, channel modernist impulses to probe national identity, despair, and deferred hope.

Their literary worlds are littered with ghosts of colonialism, war, economic quagmire, and betrayed dreams.

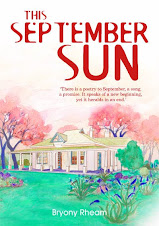

That is why Tsitsi Mutiti’s translation of Mabasa’s “Mapenzi” is crucial.

In “The Mad”, rendered into English by Mutiti after earlier efforts by Tendai Huchu, the madness is not lost but is rather reimagined.

Mutiti explained that her task was “to ferry the spirit of the book,” not just its words.

That phrase alone captures the soul of literary translation: the delicate act of carrying tone, rhythm, and cultural memory across linguistic borders without draining it of its pulse.

Mabasa confessed that early translation drafts felt “too clean, too careful,” stripping away the absurdities that gave “Mapenzi” its wild energy.

However, in the final version the balance between fidelity and freedom is restored. The English language becomes a new drumbeat for the same song: raw, unpredictable, and deeply Zimbabwean.

Memory Chirere called Mutiti’s translation of “Mapenzi” a “great piece of work” that stands “on its own the way an original piece does”.

He added: “Mutiti’s work is amazing when you realise that she is coming from the sciences, and has little or no training in translation.”

Therefore, the launch of “The Mad” marks more than a literary milestone.

It positions Zimbabwean literature squarely within the global conversation on translation, identity, and decolonial aesthetics. For too long, African literature in English has been framed through the gaze of the outsider—what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie once called “the single story.”

Mabasa’s act of translating his work, guided by his own vision, asserts agency over that narrative.

It tells the world that Zimbabwe’s stories do not need to be discovered. They only need to be heard.

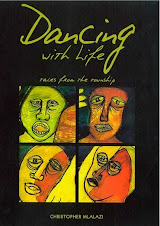

On October 17, another Zimbabwean voice spoke across continents. This time in colour, texture, and rhythm. In the tranquil setting of PaMoyo Gallery in Harare, Samantha Rumbidzai Vazhure unveiled “Nzwisa”, her debut solo exhibition which ends today.

The title itself, “Nzwisa”, invites the audience into a meditative space where art becomes a form of hearing as much as seeing. Vazhure, a self-taught painter and bilingual author, merges the sacred landscapes of Zimbabwe with the pastoral quiet of the Welsh countryside where she now lives.

In her canvases, past and present, home and exile, converge like echoes in a valley.

Each painting carries a story through visual poems that speak to identity, spirituality, and love.

In “Munhu Wangu” (2025), she captures tenderness and intimacy as communion rather than possession, while “Iwewe neni” delves into togetherness beyond the physical, suggesting a spiritual tether that defies space and circumstance.

Her piece “In the Embraces of Struggle” (2025) revisits Dambudzo Marechera’s “The House of Hunger”, turning his haunting words into a visual metaphor of intertwined histories in which black and white, coloniser and colonised, are locked forever in an unfinished embrace.

Yet, as in Marechera’s prose, there is resilience in the chaos.

In “Vapfuri Vemhangura” (2025) Vazhure honours skilled artisans of ancient Zimbabwean societies. The artwork celebrates craftsmanship, labour, and ingenuity, positioning metallurgy as both cultural heritage and a symbol of human inventiveness through the transformation of raw elements.

In traditional lore, the Soko Vhudzijena clan are praised as expert iron smelters (mhizha) who migrated from Hwedza, Mashonaland East. Similarly, the Shumba clan are said to have travelled from Mutoko through Hwedza to settle in Chivi—possibly Soko descendants who adopted the Shumba totem for strategic reasons.

Drawing inspiration from these ancestral migrations, which coincided with the southward spread of Iron Age farming, the painting depicts three men departing an iron-smelting site under the watchful protection of Chapungu, the sacred Bateleur eagle.

Though modest in scale, “Silence” (2024) communicates deep emotion through texture and tone. Set against a warm yellow background, the composition features a pair of lips—still, yet echoing the weight of words left unspoken. To one side, a mosaic of orange, red, mauve, and violet-blue textures evoke the richness and intricacy of African artistic expression.

The contrast between the vivid detailing and the muted backdrop creates an atmosphere of quiet intensity, suggesting that silence itself can carry strength, depth, and layered meaning beyond what speech can capture.

“Ziroto” (2025) speaks powerfully to Zimbabwe’s cultural psyche. Inspired by the prophecy of Chaminuka, who foresaw the coming of Europeans (those without knees), the artwork becomes a lament for historical silence.

“Who controls remembrance?” the painting seems to ask. “What happens when even our descendants no longer recognise us?”

Vazhure’s art, much like Mabasa’s writing, is an act of remembrance. It is a reclamation of the narrative from erasure. That her limited-edition prints are made from 3D scans of original paintings speaks symbolically to preservation; the attempt to retain texture and authenticity even in reproduction.

Her journey, from literary activist, author and publisher to painter since 2022, testifies to the interconnectedness of Zimbabwe’s creative spheres. Just as Mabasa moves between orality, prose, and translation, Vazhure moves between page and canvas, word and colour, as well as past and future.

Placed side by side, Mabasa’s “The Mad” and Vazhure’s “Nzwisa” demonstrate that Zimbabwe’s arts are entering a new epoch that refuses to separate literature from visual culture, intellect from emotion, or the local from the global.

Both artists confront the politics of visibility. Mabasa translates himself into English not for validation, but to occupy space in a language that once claimed ownership of his world.

On the other hand, Vazhure paints the landscapes of her memory, transforming nostalgia into resistance. In both cases, art becomes both expression and reclamation.

Their works explore a growing recognition that Zimbabwe’s literary and artistic output cannot thrive in isolation.

Collaboration between writers, translators, painters, musicians, and cultural institutions is what builds sustainable creative economies. Live music by Hope Masike at “Nzwisa” provides a sensory bridge between sound and sight—a fitting echo of Mabasa’s call for knowledge that “speaks to the people.”

Both events are crucial cultural signposts, showing how Zimbabwean art is reinventing itself as both local and global, traditional and experimental, as well as reflective and confrontational.

When one listens carefully, as “Nzwisa” urges, and reads deeply, as “The Mad” demands, one realises that both Mabasa and Vazhure are engaged in the same sacred act of translating Zimbabwe’s soul.

Indeed, creativity, like memory, is never static. It shifts form, crosses oceans, and speaks in tongues. Whether through a translated novel that carries the rhythms of Shona madness into English syntax, or through brushstrokes that merge ancestral prophecy with modern abstraction, the message is the same.

Zimbabwe’s stories still matter, and they are still being told, boldly, beautifully, and in full colour.

Even though the applause may fade at book launches and gallery openings, the larger work continues. The collective task is to sustain spaces like the National Gallery of Zimbabwe and PaMoyo Gallery to nurture publishers like Carnelian Heart, to support translators and editors such as Mutiti who make language porous, and to celebrate writers who, like Mabasa, keep pushing the boundaries of possibility.

In the end, every page turned and every canvas unveiled carries a quiet command—listen. Listen to the voices of those who dare to translate dreams into being. Listen to the madness that births meaning, and listen to Zimbabwe speaking to both itself and the world.

The Mad is co-published in Zimbabwe and the United Kingdom by amaBooks Publishers and Carnelian Heart Publishing.

Copies of the book are available in Zimbabwe through Book Fantastics (contact through @bookfantastics on Instagram, or @Book_Fantastics on X) and in the UK through Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mad-Ignatius-T-Mabasa/dp/1914287967/) or through carnelianheartpublishing.co.uk. It will be available next year in North America through the University of Georgia Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)