amaBooks holds a lot of significance for me, personally, as the first

publisher to accept my work aged 22. Every time Jane Morris (amaBooks

co-founder) and I meet, the exchanges are effervescent and full of laughter.

Here, I interview her ahead of the currently ongoing Caine Prize for African

Writing Workshop. Read an article about the workshop here.

Fungai Machirori (FM):

How is business in the publishing sector

lately? What factors are influencing this?

Jane Morris (JM): Our impression is that the

general economy of Zimbabwe is in a poor state at the moment, and obviously the

book industry is affected by this. People having less disposable income results

in less money being spent on buying books. Unfortunately reading, outside

school or college syllabi, is not a priority for many people in Zimbabwe.

’amaBooks are publishers of Zimbabwe fiction and there is a very small market

for most fiction titles.

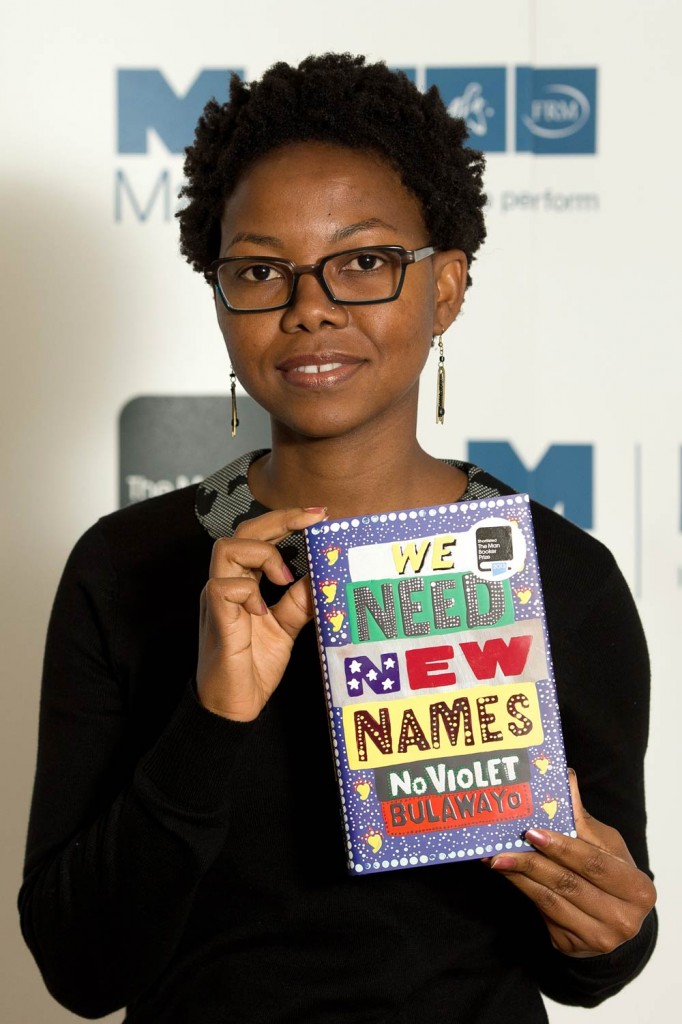

However, there are positives – success stories

such as NoViolet Bulawayo’s (We Need New Names)or Bryony Rheam’s (This

September Sun) have stimulated an interest in local literature, and the

availability of short-run printing in the region means we can continue to make

books available even if their sales are fairly limited.

FM: Are you receiving manuscripts?

Are they good? Do you have the capacity to publish?

JM: We are receiving manuscripts, and some are

of a good standard. Unfortunately with the limited sales for fiction we have to

be very selective in what we choose to publish. There have been occasions when

we have enjoyed a manuscript and would have liked to accept it for publication

but did not have the requisite resources at that time. However, the publishing

world is changing. Publishing used to depend on litho printing, which required

a large print-run in order to keep unit costs low – hence a large initial

investment. New technology has helped in that respect; a smaller print-run is

now possible, meaning that publishers can take a chance on books that are not

likely to sell in big numbers, including fiction and poetry. e-books add

another dimension, with that, and print-on-demand, books can remain in

circulation even when numbers selling are small.

FM: Are you selling many

copies locally, and why or why not? Are all the books nationally available?

JM: Our books are available in the main centres

of Bulawayo and Harare and a limited number in Mutare. We would love our books

to be available in the smaller centres, such as Gweru and Kwekwe but most

outlets only buy school text books. They are not a great number of bookshops in

Zimbabwe and we make an effort to get our books into other outlets, such as

shops selling crafts. Anyone having difficulty getting hold of one of our

titles can contact us directly. The biggest market for our books still remains

Zimbabwe. There are people in the country who do buy new books, but the number

of such buyers is limited and discerning. Efforts are being made to encourage

an interest in literature through literary events, competitions, reading clubs,

workshops and launches

We are endeavouring to enter into

co-publishing, or rights selling, arrangements to make our titles more readily

available outside Zimbabwe. Most of our books are available outside of

Zimbabwe, on a print-on-demand basis through African

Books Collective.

FM: You have turned some

books into e-books. Are they being bought? Why do you think this is the case?

What are you most popular titles currently?

Most of our books are available as e-books on a

number of platforms. Outside of Zimbabwe, e-books do seem a good proposition

cost-wise for our fiction titles, given the high cost of distribution or the

high cost of print-on-demand. Certainly, e-books sales are on the increase, we

have been heartened at some of the recent sales figures. It has also been good

to be able to bring some of our older titles back as e-books. The good news

locally is that a local company, Open Book, will soon be up and running,

selling e-books both for the standard e-readers and for cell phones that do not

need to be too smart. The option to sell either complete books and individual

stories or poems is very exciting and innovative. Worldreader are working in a

similar way to promote a reading culture, distributing Kindles in projects in

schools and elsewhere across Africa. Worldreader recently launched in Zimbabwe

at King George VI School for Children living with Physical Disabilities in

Bulawayo, and we are just about to publish a collection of stories and poems by

the students there, which will be available as an e-book.

The most successful e-book title we’ve had is

Bryony Rheam’s This September Sun, which topped sales on Amazon in the

United Kingdom in mid-2013 and remains consistently in the top 100 of Women’s

Literary Fiction.

FM: You just translated

‘Where To Now’ into Ndebele? How easy/ hard was it to get backing for this? How

do you intend to distribute this version?

JM: We have been encouraged to take the step of

publishing in isiNdebele by many writers and academics and we hope that the

publication of Siqondephi Manje? will lead to a greater interest in

reading literature for pleasure. The emphasis of publishing in indigenous

languages again seems to have been on the school market.

Literary translation is a highly skilled

activity and we’ve been fortunate in having Dr Thabisani Ndlovu, who is a

well-regarded creative writer and academic, to translate the work. Feedback

from the writers in the collection about the standard of the translation has

been very positive. The funding for the translation was part of a wider project

supporting literature in Zimbabwe.

Literary translation is a highly skilled

activity and we’ve been fortunate in having Dr Thabisani Ndlovu, who is a

well-regarded creative writer and academic, to translate the work. Feedback

from the writers in the collection about the standard of the translation has

been very positive. The funding for the translation was part of a wider project

supporting literature in Zimbabwe.

We will distribute the book through our usual

outlets, and we hope that local libraries will show an interest in the

anthology.

FM: Has the partnership with the Caine Prize

in co-publishing the Caine Prize Anthology boosted your profile and

profitability?

JM: We are delighted to be the publishers of

the Caine Prize anthology in Zimbabwe – we have always been enthusiastic about

partnerships across Africa. We wanted to bring some of the best writers from

the continent to the attention of Zimbabwean readers and this seemed an ideal

opportunity. We would also like our books to be more readily available in other

African countries and are pursuing this possibility through selling rights.

Publishing the Caine Prize anthology does raise our profile across the

continent, though, with the economic situation in Zimbabwe, sales of such

collections are limited.

FM: There are prolific

writers of fiction in Zimbabwe but most are published first outside of

Zimbabwe. Why do you think this is? And how easy/ hard is it to get local

publishing rights?

JM: Certainly many of the best-selling fiction

writers outside of Zimbabwe are those that are published outside of the country

– not surprisingly given the promotion by their international publishers, and

given the exodus of so many of the educated population and the writing

community. The most prolific Zimbabwean writers are those who tend to be

published within the country – John Eppel, Christopher Mlalazi and Shimmer

Chinodya spring to mind. With dollarization, it is becoming easier to bring

titles from outside the country to Zimbabwean readers, but the situation again

means low numbers sold.

FM: What are your hopes

for Zimbabwe’s literary sector?

JM: These are exciting times for publishing

across the world – with technological changes leading to much more open and varied

access to publishing. Zimbabwe has special challenges, due to the economic

climate, and to the exodus of many of those who write and who would purchase

literary fiction. e-book technology does seem to offer a way of distributing

content at fairly low cost to potential readers, but we must ensure that there

remains a vibrant local publishing industry that provides high quality local

literary content. There are good Zimbabwe writers, both in Zimbabwe and in the

diaspora, and we think that the future is safe in their hands. We have always

been keen to publish new writers and the ideal platform has been the series of

short writings we have published. A number of these writers have gone on to

publish their own books – Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, Bryony Rheam, Christopher

Mlalazi, Mzana Mthimkhulu, Raisedon Baya, Deon Marcus and we understand that a

number of others are working on books. We hope that this gives encouragement to

new writers following on. It is really exciting as a publisher when a

manuscript from a new writer appears on your screen, and you think … Yes.

Initiatives to encourage writing, such as the Yvonne Vera Award and the Writers

International Network Zimbabwe manuscript assessment programme are initiatives

that support and encourage writing and there is certainly the need for more of

these.

http://fungaineni.com/2014/03/28/caine-prize-writing-workshop-2014-interview-with-publisher-jane-morris/

.jpg)

.jpg)