From Borders Literature Online

Reviewed by Olatoun Williams

The glamour of the Caine Prize for African Writing is seductive, but what

made it important that I attend the SOAS readings held Tuesday 26th June 2018,

is the fact that the prize has come under fire. Some members of the African

literary community have called it ‘neo-colonial’, perpetuating

stereotypes about Africa. They argue that it is fossilized: shunning new

frontiers. One celebrated member of the community contends that an online

magazine such as Saraba does far more to promote emerging writers than The

Caine Prize for African Writing

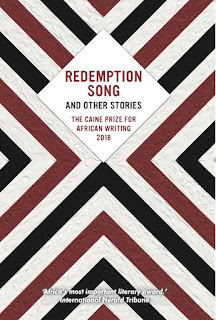

I picked up my copy of Redemption Song from the publisher,

New Internationalist, which had set up a small stand in the foyer outside SOAS’s

Khalili Lecture Theatre and went in to enjoy a short event which saw South

Africa’s Stacy Hardy and Nigeria’s Wole Talabi speaking with impressive clarity

during the plenary session. I began to read on my tube journey home. Joining

the five shortlisted stories whose authors I had just been listening to, are

twelve other stories written by authors at different stages of emergence. From

countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa,

the twelve writers convened in March earlier this year to produce short stories

at the 2018 Caine Prize Workshop held in Gisenyi, Rwanda

Given that each story is either an already

published or edited work, readers expecting high quality writing in the

anthology will find it. They will also find migration, an all too familiar

trope. American Dream (Nonyelum Ekwempu, Nigeria), America (Caroline

Numuhire, Rwanda) and Departure ( Nsah Mala,

Cameroon) tell stories dedicated to Africans in pursuit of greener pastures in

the United States of America. But despite die-hard migrants enduring

ordeals that span the predictably stressful, predictably duplicitous and

treacherous, the stories are still able to display an originality that

distinguishes them from conveyer belt trope. Departure by

Nsah Mala for example showcases a romantic love between an impecunious married

couple that is touchingly sincere and vulnerable to abuse by ruthless cynics

who are everywhere. Standing alongside these three stories are two others which

consider the subject of migration from rarely considered perspectives: ‘No

Ordinary Soiree’ helps to dislodge images from our brains of Rwandan

people damaged by a genocidal civil war. Rwandans with broken bodies and

horrifying confessions have been replaced in this tale by the affluent young

professionals of post-war Rwanda. Out of this sea of smug, well-fed faces, the

lonely face of the celebrant stands out. She is ill-at-ease, out of place at

her own birthday party. Looking around her, she confronts a truth she already

knows: marrying out of a low-income community and into the moneyed class of

society can be as isolating as migrating to another country. She has not been

able to fathom the ways of the demographic group her husband belongs to.

Ngozi by Zimbabwe’s Bongani Sibanda, presents the hardly examined trend –at

least in fiction - of intra-African resettlement. When the protagonist

family flees Mugabe’s Zimbabwe in search of sanctuary and ends up in

neighbouring South Africa, family members live out the prescriptive pain of

disappointed hopes and broken dreams. America,

produced at the Caine Prize workshop by Rwanda’s Caroline Numuhire is

particularly ironic with its soon to be jilted (and thoroughly exploited) fiancée

in rivalry with America which the author has endowed with the magnetism of an

imperious, costly seductress.

In Bringing the Clouds Home, Ethiopian Heran T. Abate spins a web of

enchantment with her presentation of the psychology of children. In this child

scale story relayed through a child’s eyes, we walk with the children,

registering things that delight them and those which inspire fear. Understanding

how cruelly excluding innocent childhood can be, readers will delight in the

evolving compassion of one little girl who befriends another whose disabilities

frighten her. Bringing the Clouds Home is Abate’s delicately told

elegy to the sweetness of childhood.

Reading like a one-woman play, Involution by Stacy Hardy

of South Africa is intellectual curiosity run amok. Hardy, an editor of the

respected Chimurenga magazine, explores the unique experience of a woman who

has found a small creature, the size of a microbe, secreted inside her vagina.

The story is amusing: cleverly and richly detailed in its examination of the

body, texture, intentions of the creature – will it breed?- and its

needs – won’t it need to eat? Those who dismiss the Caine Prize for

conservatism will repent, faced with the picture of a young woman squatting,

holding a saucer of milk to her labia lips and keeping it there for moments,

she is that serious about feeding her guest.

But if is true that poverty - bête noire of Caine Prize challengers - is

ubiquitous in the 2018 anthology, with critics denouncing this trope served up

year after year, its inevitability only exposes the truth: that poverty –

migration’s main catalyst - is not the exception in Africa but the rule. I

agree that it is crucial to display Africa’s wealth in our artistic expressions:

her tribal and language diversity, her plurality of cultures and myriad art

forms, but not at the expense of her poverty, particularly the heartbreaking

poverty of her children. It is for this reason that I welcomed Olufemi Terry’s Stickfighting

Days, (Caine Prize 2010). Terry’s terrifying portrait of street boys is

as important in its social objectives as it is masterful art.

|

| Makena Onjerika |

If the 2018 Caine Prize winner Fanta Blackcurrant did not

elicit in me the same response, it is not because the story draws attention to

Africa’s child poverty but because I questioned the idiom in which Makena

Onjerika’s children speak and behave: what is her frame of reference? That

said, scenes involving familiar, visceral human drives, elevate Fanta

Blackcurrant and we watch with the horror of recognition as the other

children, overcome by jealousy, set violently on Meri because of her ‘beautiful…

brown mzungu face’. We nod with understanding as the same children

express a compassion towards her which grows in proportion to the darkening of

her skin, the destruction of her beauty by hardship beneath the scalding sun.

And with that calamity comes the slipping away of hope of rescue from Meri’s

trembling grasp. The children are compassionate because the donors who walk and

drive past, can no longer distinguish her from the rest of them.

Bongani Sibanda’s Ngozi is centred around an idea put

forward in Fanta Blackcurrant: physical beauty as a life-line.

Though this story takes off with a Zimbabwean family in flight from cash poverty,

it quickly veers into an examination of the life outcomes of a person whose

face lacks any comeliness that would endear him to humanity. It is ugliness,

not cash poverty, which dooms the prospects of Thembani in this totally

unexpected tragedy about fraternal love and loneliness. At the broken

heart of this excellent story is an horrific crime and an ending you will not

see coming.

Beyond White Space founder, Vimbai Shire, provided oversight for the writing workshop. In

her introduction to the collection of stories produced by participants, she

comments that they ‘(tackled) the topical and the taboo’. I found this to be

true of the anthology. With a selection of four remarkable stories dedicated to

their cause, the Caine Prize has paid tribute to the brave LGBTQ voices across

Africa calling for inclusion and respect. In the eponymous Redemption

Song, Nigeria’s Arinze Ifeakandu has crafted a sensitive and compelling

domestic tragedy in which there is no mercy, no redemption for the husband who

left his wife for a young male lover and who is suddenly and tragically

bereaved of his small son. Kenya’s Troy Onyango, rising star in the literary

firmament, has bequeathed All Things Bright and Beautiful. It

weaves a rich, digressive template while retaining a compelling linearity about

a family’s collapse in the wake of the father’s suicide wearing their mother’s

white and pink-laced panties. A letter to a sibling brimming with love and

sorrow in this tragedy contains the anthology’s most heart-achingly memorable

lines.

On the Prize’s shortlist, American Dream is Nigeria’s

Nonyelum Ekwempu’s offering. While the main focus is a defenceless widow and

her small children, the author extends her compassionate gaze to homosexual

children when the young narrator finds his neighbour motionless on the floor of

his home, ‘his face swollen beyond recognition. Cuts and bruises covered his

entire body... (while) his mother seated ‘on a short stool in a corner (is)

shouting, ‘Bastard, bastard, bastard,’ repeatedly in Yoruba.’ This

disturbingly silent boy was one of two schoolboys attacked at the school by a

mob of other boys who had caught them kissing.

Nigeria’s Eloghosa Osunde has written Grief is the Gift that

Breaks the Spirit Open which falls into the afro-speculative but

Osunde, the 2017 Miles Morland Scholar, has brought into being an unusual

spirit which serially inhabits and serially dumps women’s bodies. In this

layered story, the ‘hoverer’ is a bi-sexual femme fatale with a trail of

broken hearts behind her and in front of her, a twist of irony which sees her

falling for a mirror image of herself. Erotic love is a condition that

excites in the being the desire to ground herself permanently in human flesh.

Osunde’s story is an interesting exploration of sexuality within the

intersection of the imagined ethereal with the corporeal. In this anthology

festooned with speculation, Osunde’s hoverer’s movements from an

ethereal state to the material can be categorized not only as an exploration of

identities but as a form of migration: from one condition to its opposite.

“Speculative fiction is everything that isn’t realism, and it spans the

entire continuum of the fantastic… (It is) any fiction that bends the known

world…Fantasy, I consider as a sub-genre of speculative fiction based on

imagined creatures, events, forces, people and other elements that do not come

from reasoned extrapolation of established knowledge and are presented without

respect to a scientific method” (Wole Talabi, Caine Prize 2018 shortlist).

Four stories in the 2018 Caine Prize anthology

traverse the spectrum of speculative fiction and fantasy as defined by shortlisted author

Wole Talabi at the SOAS Caine Prize readings held 26th June 2018. Grief

is the Gift that Breaks the Spirit Open by Eloghosa Osunde, mentioned

earlier, is a fantasy exploring the gravitational pull of the human body and

its constraints through the ‘human’ experience of spirit beings.

|

| Bongani Kona |

Spaceman

by Chimurenga Magazine editor, Bongani Kona from South Africa and Zimbabwe, is

a tragedy in five vignettes illuminated by a disquieting brilliance. It charts

two bizarre episodes in the histories of two unrelated groups of people: a

white South African family which, while nursing the horror of a double murder

and suicide in the family, must tolerate the presence of the family patriarch

who puts the blame for the crimes on the kaffirs. Parallel to the

breakdown of the white family, is a frantic car journey undertaken by a motley

crew of damaged African souls who have just experienced a failed attempt at

space travel in a make-shift rocket. When these haunting stories converge in

the 4th vignette, the tragic symbolism of Bongani’s outstanding fiction becomes

startlingly clear.

Where Rivers Go To Die is the gift of Ugandan Sci-fi filmmaker and speculative story writer,

Dilman Dila. It is set in a sealed off forest inhabited by a people who

venerate the organic and hand-made whilst rejecting automated machinery,

reviling it as pure evil. Dila’s story is accomplished and dense with the

perceptions of the little boy cast out by the tribal elders subsequent to his

mother’s death. The forest is dark and what appears before our squinting eyes

is a surreal tableau: a wounded little boy, taught to believe he has the

magical powers of an ‘abiba’, a ‘demi-god’, hopping about on one leg,

desperately searching in the darkness for a place to call home.

Awuor Onyango’s Tie Kidi is a gleaming, speculative wonder

which borrows liberally from Luo mythology. The world evoked here is perceived

through the eyes of a curious and adventurous girl child who can mold time and

who kicks against her confinement in a simulation tank, for her own safety. The

story looks at the present condition of an already unsustainable humanity and

projects into a future in which humanity’s survival is illogical, ‘if the

sun were truly to explode’. Wole Talabi, 2018 Caine Prize shortlisted

author, might be, as they say, emerging, but in Wednesday’s Story

he has already displayed mastery of his craft. In eighteen and a half pages,

this Nigerian author has told a story of magnificent scale based on the

well-known nursery rhyme, Solomon Grundy. In his brief biography included as a

footnote, he professes to a liking for ‘oddly-shaped things’ and ‘elegant

equations’ providing evidence in a story replete with surprising arcs and a

disorienting play with time’s equations. His love of ambitious play has made

possible a brilliant and totally unpredictable fleshing out of Solomon Grundy:

conceived here as an ochre-skinned, ankara clad child of the rape of a Yoruba

kitchen maid by an English merchant sailor.

Curiosities that defy the classifications we can fit the other stories

into are The Armed Letter Writers by Nigeria’s Olufunke Ogundimu

(shortlist) and The Weaving of Death by Rwanda’s Lucky Grace

Isingizwe. Both are testaments to the joy of story-telling but in mood and

tone, they couldn’t be further apart. The Weaving of Death is an

interesting story treating attempted suicide in the family and the emotional

travails of two siblings. At the other extreme, The Armed Letter Writers

and the inhabitants of the estate whom the thieves plan to rob, provide

farcical comedy about dysfunction and criminality in Nigeria’s law enforcement

and public service delivery. Ogundimu’s yarn is pure theatre of the absurd. It

is begging to be staged.

The Caine Prize jury has served us well with this collection of

seventeen stories whose content reads like a focused response to clamour for a

more inclusive and edgy representation of Africa: her past, her condition

today, her speculative futures; the concerns of Africans and the diverse ways

in which we look at ourselves and the world around us. To paraphrase the 2018

Jury Chair, Dinaw Mengestu, the stories in their totality put paid to the idea

that certain narratives should be relegated to the margins of our expression

and there is brave stand-out art in Redemption Song.

Redemption Song is published in Zimbabwe by amaBooks; it is available in Bulawayo at Book&Bean, Dusk Home, Indaba Book Cafe, National Gallery and Orange Elephant, or through amaBooks, and will soon be available from the National Gallery in Harare.

.jpg)

.jpg)